Jeanette Winterson: keynote speaker at this year’s 2014 Byron Bay Writers’ Festival. (Photo: David Levene, The Guardian.)

Never one to shy from controversy, Jeanette Winterson’s appearances at this year’s 2014 Byron Bay Writers’ Festival are likely to be feisty affairs, writes Digby Hildreth of the Festival’s keynote speaker.

British author Jeanette Winterson’s contribution to this weekend’s Byron Bay Writers Festival is guaranteed to be thought-provoking – and possibly provocative in other ways.

Most recently, the festival’s keynote speaker was engaged in a Twitter scrap for killing and eating a rabbit that was chomping on her parsley and roses.

She started the row by posting grisly photographs of the deceased bunny as she prepared it for the oven – anathema to some of her more politically correct admirers.

One tweeted: “You make me sick. I will never again read a word you write. Rest in peace, little rabbit.”

The heated Aga saga may have lost her a few readers but it also revealed Winterson in her true, and best, light: brave, funny, ruthlessly honest, challenging cant and wimpishness.

“Why is farmed meat fine but personally trapped disgusting? Think about it,” she retorted to the squeamish former fans.

Food and the politics around it are high up on Winterson’s list of concerns: she has even opened an outlet for organic products in East London. But she is better known for her consistently profound and insightful studies of queer and gender politics, body image, adoption and, most recently, witchcraft.

Her first novel, 1985’s Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit daringly told her own story in fictional form – how she survived an appalling adoptive childhood, marked by deprivation, abuse and extremist Christianity to emerge in her early teens as a lesbian.

Resisting the label autobiography she noted that when male authors pulled the same trick it was hailed as “meta-fiction”. The novel contained a passionate personal manifesto: “I want someone who is fierce and will love me until death and knows that love is as strong as death, and be on my side forever and ever. I want someone who will destroy and be destroyed by me.”

Winterson was born in Manchester and grew up in nearby Accrington, in the North “the dark place”, “untamed” – qualities which could be attributed to the writer and much of her work.

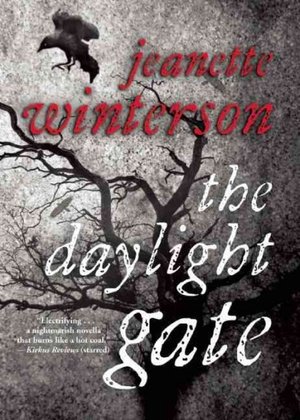

Her most recent fiction, The Daylight Gate, is a study of the horrors of 17th century witch trials in Lancashire – really a convenient excuse to persecute Catholics. It spills over with blood, torture, cruelty … every type of human vileness, redeemed somewhat by courageous characters who know that, once again, “love is as strong as death”.

There is a nine-year-old girl in it, starved, raped, half wild and half mad, who could be an echo of Winterson herself, as revealed in her autobiography, Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal? (the title is a quote from her mother, responding to Winterson’s coming out as a lesbian). Forced to sleep outside at night, or in the coal cellar, Winterson grew up tough, resilient, and damaged.

Adoption, she writes, made it “impossible to believe that anyone loves you for yourself”.

She survived it through literature, reading and memorizing poetry: “A tough life needs a tough language – and that is what poetry is.”

When her mother burns her books, it marks a breakthrough.

Standing amid the smouldering paper, she thinks: “Fuck it, I can write my own.”

Winterson is giving the Keynote speech at 11.00am on Friday August 1, and she will discuss ‘Creativity and Craziness’ with Susie Orback at the Byron Bay Writers’ Festival on Sunday August 3 at 2pm.

Digby Hildreth