Candida Baker examines the box and dice of Easter – from chocolate bunnies to the Virgin birth, and of course, what Byron Bay is famous for at Easter – Bluesfest.

“All will be well and all will be well and every kind of thing shall be well.” Julian of Norwich

When we first moved up to Byron Bay eleven years ago, with our then 13-year-old son and four-year-old daughter in tow, I never imagined that there would be an annual pilgrimage to a music festival. Somehow though, come hail or shine or mud – and there’s been plenty of all those, we’ve joined that die-hard group of fanatical believers, those thousands of us that make up the religious group the ‘Bluesfesters’, and this year will be no different.

In fact, I believe there’s actually now a second generation of Byron Bay children who actually believe that Easter IS Bluesfest.

But stomping around the Festival grounds for four or five days during what is arguably the most important religious fixture of the year, at least for Christians, does beg the question of Easter’s mixed messages.

My personal pondering on the meaning of Easter started early on. For someone who’s always had a devout belief in fairies and angels I was remarkably cynical, scarring my younger sister forever – so she says – when I discovered at five, when she was only three, that Santa Claus, or Father Christmas as we called him in England, wasn’t all he was cracked up to be. Then this Easter business was just too confusing for words. In the small village where I went to church every Sunday it was hard to put chocolate eggs, hot-cross buns, Easter bunnies, Jesus dying on a cross, and Jesus coming back to life, into a parcel that made any sort of sense. My parents, who were going through an atheist phase at the time, left me to go to church with my best friend, and were no help at all in the answering questions department.

“You’ve got a chocolate Easter egg,” my father told me one year. “Stop asking questions or I’ll take it away.” Right, well that explains that then. My mother’s complicated relationship with whisky bottles spilled over – usually literally – into a loving but incomprehensible answer to almost any question you asked. “When you ask who Jesus was,” she might say, “you’re asking was he the son of God, was he a healer – he was a Rabbi of course…” and then she’d be quite likely to wander off leaving me none the wiser.

Later on the confusion between the Jewish faith, the Catholic faith – and our particularly boring brand of Church of England faith, versus Buddhism, Allah and all the rest, left me determined to work out my own slightly peculiar set of beliefs. But at least my exposure to religion at school and church allowed me to embrace, if not God in the patriarchal sense of the word, then the idea of a divinity at work in our lives, rich in symbolism, myth and magic.

I wish the same could be said of my teenage daughter (aka The Princess), who recently moved from her public high-school to a Catholic high-school, and after some months of sickness, finally made a languid return to school for a few hours, which prompted me to be all overcome with motherly finger wagging, which went a bit like this:

Me: “So, in the brief three hours you were at school – did you actually learn anything? Anything that perhaps you might have actually, well, retained?”

Anna: “Let me see…well, I learned that Jesus wore sandals – at least I think he did.”

Me: “That comes under ‘fashion’ not education…”

Anna: “Well it’s Easter soon…that’s something to do with him isn’t it? Like, well, when he got hung on the cross.”

Me: (Gasping for breath). “Crucified. He was crucified. It’s about the crucifixion and the resurrection.”

Anna: “What’s the res-errection? It sounds rude to me.”

Me: “Anna…honestly.”

Anna: “Anyway who knows what the dude looked like. They always give him good hair, but they didn’t have iPhones then so how do you they know? He could have been bald. Also, Mum, I have to tell you – Mary weren’t no virgin.”

To be honest you can see her point. “I’d like to have been there for that conversation,” she said as she flounced off to her room full of wet towels on the floor and mugs growing mould. “Hey, Joseph, I’ve got something to tell you. I’m pregnant. It’s not yours – but GUESS WHAT – IT’S GOD’S! Way to go Mary…”

The Princess is firmly devoted to the idea of Bluesfest as her pagan Easter ritual festival. She might not have realised it, but last year when Hozier sung his anthem ‘Take me to Church’, there was a sudden and extraordinary meeting of the sacred and profane right there in a tent full of thousands of people:

Take me to church

I’ll worship like a dog at the shrine of your lies

I’ll tell you my sins and you can sharpen your knife

Offer me that deathless death

Good God, let me give you my life

If I’m a pagan of the good times

My lover’s the sunlight

To keep the Goddess on my side

She demands a sacrifice

She. God. Goddess. We tend to think of feminism as a recent development, or at least, those of who remember the days before iPhones do, but to put on a feminist hat for a moment, Easter is one more example of a pagan celebration that was originally connected to women, but was hijacked over the centuries by the patriarchy to the point where I think you would have a hard time finding even one child who would know that in fact Easter was originally a celebration of spring and fertility. Its name comes from the Saxon goddess of the dawn and spring – Oestre or Eastre, who was known also in Germany as Ostara, Easter connecting to the word ‘estrogen’, or oestrogen, to give it its older spelling. In Saxon times April was called ‘Ostermonud’ the month in which the cold winds of winter stopped, and the spring began.

But deep feminine wisdom goes back, as it should, to the dawn of time (as indeed, of course, does deep male wisdom). There are many female mystics who have been forgotten, or ignored, by mainstream education.

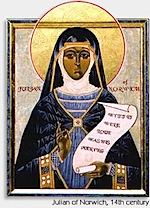

Take for instance, the wonderful Julian of Norwich. We don’t know much about Julian’s life – even her name was simply a reference to the Church of St. Julian in Norwich to which she attached herself, cloistering herself forever inside a small stone anchorage built against the outer wall of the sanctuary. By the time Julian entered her cell she had witnessed three rounds of Plague, had almost certainly lost most of her family and loved ones, and had nearly died herself.

But she even prior to the desolate landscape that may have led her towards her solitary life, when she was young she already showed signs of devotion to Christ, saying that she had been asked to bear witness to the passion of Jesus. When she was on her deathbed the visions she had were of Jesus’ crucifixion, which she felt in every cell of her own body. Other saints and mystics have reported similar experiences, but what is unusual about Julian’s story is that Jesus’ death was not distressing to her. It wasn’t, she says, that he didn’t suffer but rather despite the suffering, he also radiated warmth, sweetness, and joy.

Take ‘sin’ for instance. Sin, says Julian, turns out to be “no thing.” She is quite clear: “Nowhere in all that was revealed to me did I see a trace of sin,” she writes. “And so I stopped looking for it and moved on, placing myself in God’s hand, allowing him to show me what he wanted me to see.” In Julian’s view, “sin has no substance, not a particle of being, and can only be detected by the pain it causes.” When we make mistakes and create suffering or suffer ourselves, we humble ourselves and God loves us even more. If your leanings are towards a more contemporary church, try substituting the word ‘sin’ for shame, or blame.

But for me what is perhaps most startling about Julian’s theology is her view of the feminine identity of God. Julian still sees the Godhead in the Christian Trinity – traditionally ‘The Father, Son and the Holy Spirit’, but with this twist: the Second Person (Christ) is actually the Mother (not the Son). In other words: ‘The Father, Mother and the Holy Spirit’.

“As truly as God is our Father,” she says, “just as truly is God our Mother.” Who else but a mother, she asks, would break herself open and pour herself out for her children? “Only God could ever perform such duty.” Not only that, but Julian’s God-as-Mother is always available to us. She encompasses the unconditional love of Mother Mary in the Catholic tradition, the infinite compassion of Tara in the Buddhist tradition, and the holiness of the Shekhinah in the Jewish tradition. It bemuses Julian that we don’t understand this. When we get something wrong, we want to run away. But “our courteous Mother doesn’t want us to flee,” Julian says. “Nothing would distress her more. She wants us to behave as a child would when he is upset or afraid: rush with all our might into the arms of the Mother.”

For Julian, the good news is not merely the reward we will receive one day when we slough off this mortal coil and go home to God. Every moment is an opportunity to remember that we are perfectly loved and perfectly lovable, just as we are. Living ‘in the present moment’, it would appear, has been around for a while.

“And so when the final judgment comes,” Julian writes at the end of The Showings, “… we shall clearly see in God all the secrets that are hidden from us now. Then none of us will be moved in any way to say, ‘Lord, if only things had been different, all would have been well.’ Instead, we shall all proclaim in one voice, “‘Beloved One, may you be blessed, because it is so: ALL IS WELL.'”

It may occur to readers to wonder where I’m going with all of this, but it’s simple really, what I found in the feminine mystics – particularly in the sacred music of Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179), also known as Saint Hildegard and Sibyl of the Rhine, who was a German Benedictine abbess, writer, composer, philosopher, Christian mystic, visionary and the founder of scientific natural history in Germany – was the Missing Link. The Divine Feminine that allowed me to understand the depths of mysticism from which all religions springs.

In their different ways, visionaries like Richeldis de Faverches (founder of the Holy House at Walsingham, or ‘England’s Nazareth’), the learned Hildegard of Bingen, Hadewijch of Brabant (exemplary voice of the Beguine tradition of love mysticism), charismatic traveller and pilgrim Margery Kempe and anchoress Julian of Norwich all challenged traditional male scholastic theology.

So it was with delight that when I was ‘tagged’ by the photographer Juno Gemes in her extraordinary photograph of a female Christ in ‘Bush Pieta’, I found the perfect image for this piece. The powerful transformation from the traditional pieta of Mary cradling the dead body of her son, Jesus, to Joseph cradling the body of his dead daughter, holds for me the divine duality of life.

So to take this piece back to where it started, when I’m lining up for hours for a Byron Organic Doughnut, or sloshing through the almost-inevitable mud, or there for the moment when a band, or a singer, reaches the heavenly heights, Easter for me is a time to reflect on this – life, death and rebirth.

Happy Easter.

Candida Baker’s next set of Just Write courses start this week: https://www.verandahmagazine.com.au/just-write/