The post Accidental Grace appeared first on .

]]>You can see more of Kim’s soulful work on: https://www.kimcarey.com.au/booksebooks.html

The post Accidental Grace appeared first on .

]]>The post Heartbreak grape at the Whipbird Winery appeared first on .

]]>Launching the new novel from Bangalow author Robert Drewe at the Byron Writers Festival recently, eminent critic Geordie Williamson noted that the pinot noir grape is known as the “heartbreak” grape – notoriously difficult to grow.

He did so because it’s the variety chosen for cultivation at Whipbird, the vineyard being developed by Hugh Cleary, the self-consciously aspirational protagonist of Drewe’s book of the same name.

Hugh’s choice suits Drewe’s satirical purpose: Whipbird is located near Ballarat, a region that has attracted investment in recent years for its suitability for the pinot noir grape. That suitability has been improved by the advent of climate change, a warming which Hugh welcomes with solipsistic complacency: “Now the adjusted climate… has made Whipbird uniquely suited to growing pinot noir grapes,” he tells guests – and potential Chinese investors.

That adjusted climate is sheer brilliance, the weasel words of the investment wanker.

“I foresee a deep crimson-purple wine, with the foresty-savoury density that’s the hallmark of the region, underpinning a long, black-cherry-filled palate,” continues Hugh, successful lawyer and wannabe vintner, “all smiles in his weekend rustic clothing”.

So, blend in wine snobbery to the food fads, mammalian meat allergies, private schoolboy rock bands with names like Wasted Promise and Malice Aforethought, doped up surfers seeing yowies in the night, Gold Coast cougars, “distressed” antiques – the ephemera of the age – that make up the comic feast of this novel.

Underlying all this is the more deeply felt satire, aimed at the era’s hubris, its narcissism and individualism, the breakdown of good old Aussie egalitarianism, fairness and decency.

Whipbird is the setting for the action in the story – a vastly scaled reunion of the descendants of Irishman Conor Cleary, who made his way to the new world within the British Army 160 years earlier.

There’s more than a thousand of them, their dress colour-coded to differentiate each familial line, come to imbibe and ingest the offerings from a dozen barbecues, (or, for the vegans, the blistered kale and quinoa pancakes fom Agrarian Revolution) and gossip and backbite.

Hugh’s immediate family comprises an irritable and distracted wife, vegetarian teenaged daughters, son in search of carnal knowledge, a brilliant but frustrated sister (carrying the Irish disease, haematomachrosis).

More graphically, a brother, Sly, former member and victim of the briefly blooming pop-rock band Spider Flower (whose hits included Tight Tight Jeans, Face First and You Want it So Bad), who is suffering from a disorder that makes him think he’s dead; and dad, Mick, an old school decent bloke, but a bitter reject from banking – once a service, now an industry, with no place for “customer-first” types like him.

Mick – Drewe’s most sympathetic character – and the man who chucked him, Doug, his cousin, don’t converse about football, they make bald statements of “fact” at each other, as men do, each hoping to sound the more authoritative.

Such passive-aggressive competitiveness – a function of gentrification, materialism and, surely, the Australian character – rears up in scene after scene: a sub-text to the reunion invitation was that “so many of them were doing so much better than they were in 2004”).

Other certainties – that toxin to conversation – are cleverly scripted: aunties in mobility scooters grumpily agree on the poor choice of the “dull” whipbird as viagra pas cher the estate’s name, but one-up each other over whether WA’s Splendid Fairy Wren or the Victorian specimen is the prettier bird.

There’s competition too, between the certainties of the past and the received correctness of the present – providing both a nostalgic undercurrent of some poignancy, and another opportunity to lampoon both contemporary fads and foibles, and the wrong-headedness of our forebears.

For instance, Whipbird estate is located near Ballarat, at Kungadgee – a Wathaurong word heard frequently, and misunderstood, by the region’s first Europeans; it means goodbye!.

Much of the story and history belong to Victoria. There’s Richmond, and its early settlement by the Irish, who moved effortlessly up the social scale, from Conor, like so many forced by poverty to take the king’s shilling and end up shooting at his own countrymen at the Eureka Stockade, through Tigers footballers, bankers and lawyers like Hugh, whose pretentious “homestead” is light years away from the old sod.

The Northern Rivers doesn’t escape the satirical examination either: “I think a bloody dolphin could be elected mayor here if they wanted the job,” yells one disillusioned sea-changer.” But while some of our behaviours are ridiculed, as with the Melbourne mob, it is gently done.

Ireland is treated sympathetically – this after all is the land of Drewe’s ancestors too, and the reunion’s randy raison d’etre, old Conor, is based upon his own great-grandfather, who sired 15 children, the last of them when he was 70. In a secondary story, County Tipperary provides the setting for the drunken catharsis of an army priest, burned out after pastoral duties in Afghanistan.

Conor’s descendants are now, like Drewe, deeply familiar with the footy field, the surf and the bush. This is an insider’s account. Although Drewe set out to put contemporary Australia “on the slab”, to highlight its absurdities and affectations, it is done more so in affection than in anger; the author admits to having had a lot of fun writing it, and that defines the over-arching tone.

However, while this is undoubtedly a comic novel, laugh out loud funny, it manages to also be a story of considerable depth: several story lines come to an end, there is revelation, redemption, closure.

It makes for a thoroughly satisfying read, on a number of levels.

To order Robert Drewe’s Whipbird go to: penguin.com.au/books/whipbird

The post Heartbreak grape at the Whipbird Winery appeared first on .

]]>The post Decades of Deadlines give way to the Writing Life appeared first on .

]]>“I’ve been to almost every one since the second festival, and I’ve always been thrilled to be part of it – it almost feels like home,” Susan Wyndham, the recently retired literary editor of the Sydney Morning Herald tells me on the morning she’s getting ready to fly from her home in Sydney up to Byron Bay. Like many other participants of the early festivals one of her most vivid memories is how cold the old resort used to be – so much so that for the first festival Helen Garner went out and bought hot water bottles for the writers!

“The other thing I remember about the old days was how dark it used to be trying to get around the site at night,” she recalls. “In fact I actually remember one year trying to find my cabin and triumphantly thinking I’d arrived, only to burst in on Hilary McPhee and Don Watson who looked very surprised.”

Twenty years on and much has changed, including the now palatial surroundings of the new resort Elements, to the amount of marquees and participants. But the ethos remains the same says Wyndham. “The great thing about the Byron Bay festival is that it was so grounded in the local environment – it was truly brilliant right from the start, and now that it’s grown to its rather grand size they’re still managing to keep the atmosphere, which can’t be an easy balance to find.”

Wyndham has high praise for the Byron Bay Writers’ Festival. “I love its informal atmosphere, the quality of the presenters – and of course when the sun shines, it has to be the best festival in Australia,” she says, “and it looks as if we are going to be lucky this year.”

At first glance it’s not difficult to spot that there is quite a high proportion of journalist/writers on the program – participants such as Jennifer Byrne, Matt Condon, Tony Jones, John Lyons and Susan herself, and although of course they have all written books I wonder if the demarcation between journalist and writer has softened somewhat over the decades.

“I think that what is interesting is that the world is giving us more and more extraordinary stories,” she says reflectively, “almost more extraordinary than fiction itself, so the reporting of those stories and the journalism around them have meant that the non-fiction element of festivals has become stronger and stronger, and I think that’s a great thing.”

One of the pluses too about coming to Byron, Wyndham says, is the feisty nature of the debate she’s seen there over the years. “I think because the Byron population is by its very nature so politicised it makes for great audience participation and lively discussion,” she says. “It’s been a politically aware festival right from the beginning and as environmental issues have gained so much importance in the public arena, the festival has been there as a place for public discussion.” She pauses. “Even if almost everybody is, shall we say, on the same side.”

For Wyndham there is a slightly bitter-sweet note to her attendance this year. Having watched several rounds of Fairfax redundancies, she finally made the decision to leave her position as Literary Editor of the Sydney Morning Herald earlier this year. “It was a very hard decision to leave the paper that’s been most of my life,” she says, “but I must say once I was out of the door I’ve never looked back. I thought it would be tough adjusting to life outside after 35 years of full time work, but I have to say I’ve adjusted very easily!”

Not that she’s without company at home – there is her husband, fellow journalist and writer Paul Sheehan, and there is Leo – a handsome black and white cat who has made himself quite a presence on Wyndham’s Facebook page, frequently for doing what cats do best of all – interrupting her work.

Ironically the couple were determined to stay an animal-free household, but Leo had other ideas. “We never wanted an animal,” she says. “Leo was living five doors down the road, and was perfectly happy but then the household he was in got two more cats, and I think he simply decided he wasn’t going to share. He worked his way up the street until he found us – two nice middle-aged people, with no cats, dogs, or children! We steadfastly refused to feed him, but he’d come in and sleep on the bed anyway, and eventually our neighbour decided he’d moved and brought all his stuff down to us.”

Leo is ‘helping’ Wyndham write the novel that she’s had in her mind for many years mostly by sitting on her keyboard at every opportunity. “Of course I always used the excuse that I was in full-time work,” she says, “and now I can’t do that, but I have to learn how to give my writing the space and time it needs. After so many decades of deadlines it’s wonderful to be able to sit and think and to allow ideas to develop.”

It’s easy to see that with Wyndham’s long-term literary connections and her writing and chairing ability why she is in high-demand at festivals, and as a contributor, but she worries about the broader picture of journalism. “I had a great career at the Herald and more briefly at the Australian,” she says, “and I was lucky to be part of that great era of journalism. But for a lot of my younger colleagues it’s been a terrible shock to the system to them to lose their jobs. I just live in hope that journalism will continue to reinvent itself.”

At the festival Wyndham is in two conversations – one with Brisbane-based writer Ashley Hay, whose third novel 100 Small Lessons has recently been published, and one with Jane Hutcheon, whose book China Baby Love chronicles the story of Linda McCarthy Shum, the Australian woman who has worked in China for the past 20 years helping improve conditions for orphans.

She is also launching a book of Thea Astley’s collected poems as a prelude to this year’s Thea Astley lecture which will be given by Peter Fitzsimons and is taking part in a panel organized by the Copyright Council – The book that changed me, with Barry Jones and Tracy Spicer.

Any last words before she goes to catch her plane? She pauses. “Yes,” she says. “I’ve checked out the weather reports and I’ve been very brave and left my gumboots behind.”

For more information on the Byron Bay Writers’ Festival go here: byronwritersfestival.com

The post Decades of Deadlines give way to the Writing Life appeared first on .

]]>The post A Bob or Tim by any other name would be round or thin? appeared first on .

]]>Don’t you love complex scientific research that spends time and money to come up with results that everyone knows already? Like the recent buttered toast study, where several scientific investigations found that grandma was right: toast dropped from a table falls butter-or-jam-side down at least 62 per cent of the time.

Then there was my favourite research study of 2016: the finding by St Andrew’s and Glasgow universities that the opposite sex becomes more than 25 per cent more attractive to people drinking alcohol.

A corresponding study at Bristol University went even further, discovering that students of both sexes found people 10 per cent sexier after just a measly 15 minutes of drinking and two beers. (Also proving that British universities have no trouble signing up willing students as research subjects.)Now, on a different tack, a major study involving hundreds of participants and researchers in France, Israel and the US, and just published by the American Psychological Association, has discovered that people often look like their names; specifically that men named Bob mostly look like men named Bob, and that Tims actually look like chaps called Tim.

Putting aside the question of why an international Bob and Tim research study should be conducted in the first place, the investigation found that participants shown a photograph and given a list of five names, matched photographs of the Tims and Bobs to their names with 40 per cent accuracy. Furthermore, a computer using a learning algorithm matched 94,000 facial images to their correct names 64 per cent of the time.According to the chief researcher, Dr Yonat Zwebner of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, this was because of the cultural stereotypes we attach to names. People subconsciously altered their appearance to conform to the cultural norms and cues associated with their names: “Those areas of the face controlled by the individual, such as hairstyle,were sufficient to produce the effect,” said Dr Zwebner.

Dr Ruth Mayo, co-author of the Bob and Tim study, says we’re subject to social structuring from the minute we’re born, not only by gender, ethnicity and socio-economic status but by the simple choice our parents made in giving us our name. “These findings suggest that facial appearance represents social expectations of how a person with a particular name should look. A social tag may influence one’s facial appearance and our facial features may change over the years to eventually represent the expectations of how we should look.”

And why were people able to differentiate a Bob from a Tim? Because, the study found, Bob was “a round-sounding name” so Bobs were thought to have round faces, while Tim “sounded thin”, with a narrow face. ‘

Hmm. Speaking as a Robert or Rob (not a Bob, thanks), it seems to me the study missed an important point. The parents who apparently laid down these rules when naming their boy babies, would actually have called them Robert and Timothy, not Bob and Tim, maybe with quite different cultural and social expectations.According to the Behind the Name website published simultaneously in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, the “popularity ratings” given by hundreds of respondents to Bob and Robert, and Tim and Timothy, vary considerably.

Robert scores magnificently for Masculine, Strong, Classic, Mature, Wholesome, Refined, Serious and (oh, oh) Nerdy. Bob, alas, while also getting a Masculine, Strong and Wholesome rating, features mainly in the Informal, Common, Rough, Boring, Comedic, Simple and Unintellectual departments.

Of course this is unfair and very, very wrong. Especially the fat-faced, Boring, levitra and alcohol Common, Simple, Rough and Unintellectual slurs. Amongst many other fabulous exemplars of the name, let me hasten to present Bob Dylan, Bob Hawke, Bob Marley, Bob Hope, Bob Carr, Bob Ellis and Bob Woodward.

Similarly, although Tim scores well in the Youthful, Masculine, Strong, Informal, Wholesome, Comedic and (oh, oh) Nerdy polls, Timothy’s ratings in the Mature, Classic, Refined and Intellectual departments beat Tim’s and Robert’s names (and, of course, poor Bob’s) hands down.

All of which should be taken with a pinch of salt when you consider that perhaps Australia’s two favourite sons, intellectual and otherwise, are the Tims Minchin and Winton.

Incidentally, the Behind the Name site has some interesting respondents’ ratings for the name Donald. Published two years before the US election, the areas in which Donald dominated are Bad Name, Feminine, Modern, Informal, Common, Urban, Devious, Rough, Simple, Comedic, Unintellectual and Strange.

(Sincere apologies to the Dons Bradman, Corleone, Quixote, Draper, Pleasence, Chipp, Sutherland, O’Connor and Duck.)

Robert Drewe’s long-awaited new novel WHIPBIRD will be published by Penguin/Viking on July 31: penguin.com.au/books/whipbird-9780670070619

The post A Bob or Tim by any other name would be round or thin? appeared first on .

]]>The post Creative Courage – an inspiratonal writing journey with Candida Baker appeared first on .

]]>What exactly is creativity? Or, even more importantly – what is our own unique, individual creativity, and how do we tap into it, to find a deeper, more authentic way to live. Creativity helps us see the world in new and different ways – to use an abstract, conceptual way of thinking that helps us bring surprising solutions to our problems.

Writing is one of the most powerful ways to access creativity – of all kinds.

Through writing we can access the deepest desires of our soul and bring them to the light. So bring your Creative Courage to the table, and join us in a six-week feast for the senses!

What previous participants have said:

“Inspirational,” India Morris, Australia

“The entire course was bliss – from the first moment to the last,” Cecilie Brown, Spain

Candida Baker is a writer, publisher, editor and ‘horse listener’, and

the author of numerous fiction, non-fiction and children’s books.

Her latest book is Belinda the Ninja Ballerina.

She holds an MA in Art History from the University of Adelaide.

For more information email Candida on: [email protected]

Or call her on: 0401056894. Websites: www.candidabaker.com

Date: Every Tuesday from November 8, or every Thursday November 10

Time: 1.00pm-2.30 pm Tuesdays, 7.30-9.00 Thursdays

Online Cost: $380

The post Creative Courage – an inspiratonal writing journey with Candida Baker appeared first on .

]]>The post Creative Courage – an inspiratonal writing journey with Candida Baker appeared first on .

]]>What exactly is creativity? Or, even more importantly – what is our own unique, individual creativity, and how do we tap into it, to find a deeper, more authentic way to live. Creativity helps us see the world in new and different ways – to use an abstract, conceptual way of thinking that helps us bring surprising solutions to our problems.

Writing is one of the most powerful ways to access creativity – of all kinds.

Through writing we can access the deepest desires of our soul and bring them to the light. So bring your Creative Courage to the table, and join us in a six-week feast for the senses!

What previous participants have said:

“Inspirational,” India Morris, Australia

“The entire course was bliss – from the first moment to the last,” Cecilie Brown, Spain

Candida Baker is a writer, publisher, editor and ‘horse listener’, and

the author of numerous fiction, non-fiction and children’s books.

Her latest book is Belinda the Ninja Ballerina.

She holds an MA in Art History from the University of Adelaide.

For more information email Candida on: [email protected]

Or call her on: 0401056894. Websites: www.candidabaker.com

Date: Every Tuesday from October 18 – November 29

Time: 7.30-9.00pm online Cost: $380

The post Creative Courage – an inspiratonal writing journey with Candida Baker appeared first on .

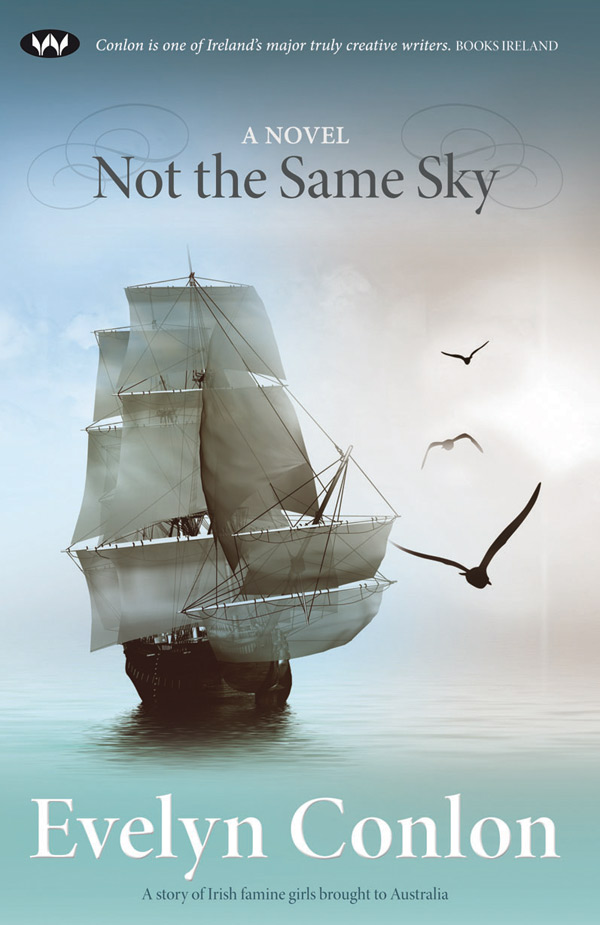

]]>The post Evelyn Conlon on imagining Byron, festivals, prizes and more appeared first on .

]]>It was while getting ready for the dive into the shadowy waters of publishing PR that Byron Bay came into my head. My memory can hatch it quite well when walking around Rathmines in Dublin, although clearly I don’t think about it every day, that might be a bit odd. I was on a comparison kick so indulged myself a bit, having just finished a series of radio essays comparing like things, for instance Independent Bookshops – one in Liverpool, News from Nowhere and one in Dublin Books Upstairs, terrific places that somehow or another have survived the attempted blanching of all things literary.

I also wrote one about two Blayneys, one beside where I was born in Monaghan and one in NSW. There’s nothing that joins them really except their names, the fact that their populations are 3355 and 3634 and that I wanted to write about them in order to have an excuse, in a Dublin winter, to imagine grass white with sun, and immense cloud free skies that drop into eternity. It’s a long time between the beginning of Autumn and June, when suddenly the flowers are all broken out of the ground, it’s bright until 10pm and then10.30 and then later still, until we can stretch it to 11pm or more out on the West coast of Ireland. As you can see I’m a successful bilocational sort of person, without having to do the flight. But then, like at this minute, that’s what writers do, imagine themselves to be someone else sending long distance messages in bottles.

Edwin Hayes: An Emigrant Ship, Dublin Bay, Sunset, 1853. Evelyn Conlon chose to talk about the painting from the National Gallery of Ireland because of the material in her novel, Not the Same Sky.

That morning had begun optimistically enough, the occasional last surprising gold leaf fluttering from the tree – we had thought them all gone, but no, some slow ones, maybe caught in a late thinking, hiding up in the branches for some final rumination, take their time before diving to the ground to begin a different life. The National Gallery of Ireland had decided to celebrate its 150th birthday by having a number of writers respond to a painting in their collection, and as one of the writers I had been asked to speak about why I had written what I had written. So I almost missed perhaps the very final leaf flying its solo dash through Stephen’s Green. I talked my talk and questions came from the floor and I was suddenly in Australia again. I suppose I should not have been surprised about how quickly that happened but I was. I had chosen two paintings one looking at the other, and a character from one speaking to the other. The paintings are A Lady Holding a Doll’s Rattle, 1885, by Sarah Purser and An Emigrant Ship, Dublin Bay, Sunset, 1853, by Edwin Hayes. The reason I had chosen the Edwin Hayes is because of the material that I had been soaked in for years now, all associated with my novel Not the Same Sky which tries to brushstroke the life of Irish Famine girls being brought on 21 ships to a place called Australia. Imagine that. (If I’d been asked now I might have chosen differently, because I’m lost in the world of the Irish woman who attempted to assassinate Mussolini and nearly blooming succeeded. There’s another thing to imagine. What if she had.) But that morning we had a wonderful hour in the National Gallery trying to tease out what we thought those girls memories may have added to your history.

The fright of the PR to come is what took me back in time to bookshops that do their work and know their staunch readers and what they might like. Like many writers I balk at PR, it’s the opposite of what we do . When asked what prizes I think a book should be entered for, I hesitate because oh I do hate them. I hate what they’ve done to reading, what they’ve done to writers. And although I understand that they can be a method of bringing attention to the as yet unknown, when the bookshop experience seems like you’ve been tipped into a tombola then clearly we have lost sight of the art of finding our own books. Bookshops are supposed to be places where we get lost, they should have a touch of Hundertwasser about them. There should be a slight secrecy attached to finding a book, just the one we need at that time. We should not be bulldozed by giddy marketing.

I know that discussing the present hurricane of prizes may seem like a hefty jump from walking into a bookshop but I think not. I am of course seriously aware that this is a very tricky area for a writer to touch – we don’t do it because we are afraid of being accused of having sour grapes. But I’ll chance it, because far too many of us are being silenced by this tyranny and are afraid to be counted as skeptics. I see the over-emphasis of prizes as the devaluation of all those wonderful mysteries we were out looking for. For all that hope flying in on wings. For the expectation that we would have to search for a book that might satisfy our particular curiosities. Now there seems to be a conspiracy to have us all reading the same book at the same time. What could be more awful, more anathema to a non-school-goer’s right to life? (The exception to this is at Literary Festival Time, because that’s the terrific point of them, a sort of concert of reading where you’re nodding to a shared rhythm.) Leaving aside the fact that, yes, a Prize listing has become the new essential, consider for a moment what multinational publishing company has control over what is even allowed to be entered, never mind make it for consideration. And if you find this hard to believe just think of the system devised to find our first human to head to Mars. (In case you haven’t heard, the Irishman on the list, Joseph Roche, has just blown the lid on the crowdfunding aspect of the procedure. I am not joking. There’s a top 99 list now. ) Fay Weldon once remarked that prize ceremonies were not so much about rewarding the chosen winner but more about watching the cheque being snatched away from the others on the list. Or, as she recently remembered it to me…book prizes are rather like a dog show: a great entertainment at the expense of the writers. The leading writers of the land on show to have their disappointment viewed while all but one fails win.

And why did Byron Bay come back into my head? Because in looking for correspondence that I need for the job of shipping this novel out into Irish reading I came across emails from your bookshop. That time I visited, 2011, there had been one of those weird publisher/ distributor secret rows and my books did not arrive in time, despite all the hard work of the jolly happy book shop in Byron Bay. Let’s hope we arrive at the same time this year. I will soon begin to prepare, while I sadly salute my friend Paul Cox, whom I met at Byron Bay last time.

I don’t know all your bookshops – I did not have enough time – but I presume you treasure them. There’s an astonishing image from the book, An Evil Cradling, which Brian Keenan wrote about his hostage captivity in Lebanon. A bowl of fruit is left before him and although he really desires and needs it he wants to keep the orange uneaten because the colour will last longer if he doesn’t peel it. The colour was essential to his living. So are bookshops. If you’ve ever looked up at the swishing sound a flock of birds make you will know that it leaves a freedom in its wake. It rustles the air around you. Becoming missing in your local bookshop can do that too.

Evelyn Conlon, Her latest novel, Not the Same Sky, was published by Wakefield Press, 2013, and released in Ireland in 2015. Details on www.evelynconlon.com She will be attending the 2016 Byron Bay Writers’ Festival, participating and giving a workshop. Go to byronwritersfestival

The post Evelyn Conlon on imagining Byron, festivals, prizes and more appeared first on .

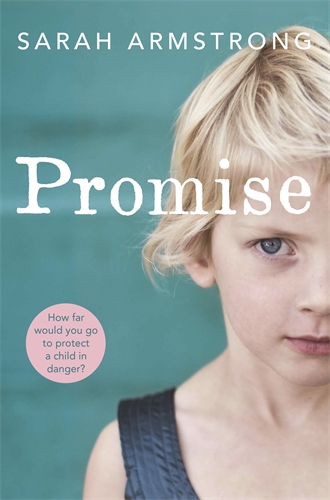

]]>The post Sarah Armstrong’s magical Mullum delivers her promise… appeared first on .

]]>The month I started work on my first novel, I moved from a small Sydney apartment to a ramshackle cottage in a rainforest valley near Mullumbimby. Tall trees reached their branches over our roof, and at night we could hear animals – possums, bandicoots, pademelons – rustling around in the forest just twenty metres away. Not long after we moved in, it started to rain. And didn’t stop for three months.

The landscape and the rain – perhaps predictably – found their way into my book; Salt Rain featured lots of dripping forests and red mud and creeks rising over causeways.

After a couple of years I left the valley – because my marriage ended – and moved to the coast, near Byron.That was sixteen years ago and since then I’ve lived down on the plain, mostly in the township of Mullumbimby. But I can’t seem to stop writing about the valley. It has featured in all three of my novels and in several stories. Now – about to embark on my fourth novel – I’m trying to understand what it is about the hills that has so captured my imagination.

* * * * * *

I grew up in Armidale, New South Wales – sheep country with distant blue hills and vast open paddocks. When my family would drive to the coast for a camping holiday, I avoided looking out the window at the dry paddocks and sparse eucalypts because something about them made my stomach feel hollow. I longed for the lush, dense vegetation of Valla Beach where we were headed.

In my new novel, Promise (set largely in the hills around Mullumbimby), my protagonist, Anna, walks into a forest:

The dirt path was narrow and wound between the tall trees. All around, the air was wet and loamy, and rain dripped from the forest canopy above, the droplets bouncing the big leaves and making the delicate ferns shiver. It was such a benign landscape. No, it was more than benign, it was abundant and cocooning. Which was why she was desperate to stay and not head out into open country.

Anna once read that people were meant to be feel most at home in the landscape of their childhood, but she found the countryside around Orange uninviting.

Here, the forest burst with life, everything moist and fertile, vines looping from tree to tree, ferns and palms sprouting from the smallest crevice. When she was nineteen and Pat first drove her up into the hills in his old van, the forest getting denser around them by the minute, the thought kept running through her head, I’ve come home, I’ve come home.

While not autobiographical, my novels inevitably explore ideas that fascinate and preoccupy me. Like Anna, when I first drove up into the hills behind Mullumbimby, in a real estate agent’s leather-seated car, I had the sense of returning home.

My then-husband Matt and I bought the one-bedroom cottage the real estate agent showed us. I left my job at the ABC, we followed the removal truck up the highway and set to work painting the cottage, building a deck and planting a vegetable garden.

I can still conjure clear memories from that January, of walking down to the waterhole each afternoon, along the winding dirt road, past the hillside of palms, to the burbling, boulder-strewn creek. Sweaty and tired after working on the house, we would sink into the cool, earthy-smelling water. The creek rushed over a lip of rock into the big still pool where I floated on my back, looking up to the trees circling the waterhole, their branches silhouetted against the sky. I felt protected and contained by the trees and the valley walls, and by the quiet. It was unfathomable that my friends and colleagues were – at that very moment – driving through traffic in Sydney, and rushing to story deadlines at the ABC. Up in the hills, I felt outside time. Like I’d entered a magical realm.

When the rains came, we learned to keep working outside even as it bucketed down, we learned to navigate the slippery red mud, and to stock up the pantry in case the creek crossings went under or a tree fell over the road. Neighbours told me stories of having to walk for hours through the bush to reach town for urgently needed medication, and I heard of flying foxes used to cross flooded creeks and cars washed off the causeways. There was something thrilling about being cut off from the rest of the world, about having a heightened awareness of the weather and landscape.

I suspect that sense of the thrilling is one reason why the hills hold a special significance for me. There’s a profound appeal in the idea of being self sufficient and beyond the usual demands of society.

I also felt in contact with nature there in a way that I’ve not experienced since. Nature is dramatic and unavoidable in the hills. Trees crash in the forest, flooded creeks tumble boulders about like marbles, and all around are snakes and leeches and ticks. Before my eyes I saw nature reclaiming its land, land that had long ago been cleared by white settlers for logging, then banana plantations and dairy farming.

Anna knew there were hundreds of houses tucked into the folds of the valleys around here. The farmers had sold out to hippies who built ramshackle homes from secondhand materials and lost control of the weeds, especially the lantana. The seed bank in the soil had sprouted with native trees and exotics like camphor laurel, and now the hills were thick with trees again. Most of the houses Anna had visited the year she spent with Pat had been unlined or works-in-progress. She’d found it very romantic, the idea of crafting your own home, forging your own way, not following someone else’s ideas of a successful life. This secluded valley was now a perfect place for Anna and Charlie to hide.

Perhaps, above all, the valley was a place for me to retreat from the world and from a busy, deadline-driven life. At times, these days – my time consumed by mothering and writing and running a house with my partner, Alan – I long for a simpler, quieter life, hidden away among the trees. But, interestingly, I rarely visit the valley (and I live only twenty minutes away) and have never contemplated returning to live there. Maybe I don’t need to visit. Maybe it lives more powerfully and magically in my imagination; maybe it’s taken on a life of its own there. Sometimes I wonder if the people who live in the valley now might not recognise my version of it.

It was the most exhilarating landscape I’ve lived in, and I think I continue to write about it because when a landscape exerts a powerful influence on a character, the writer has more scope for drama and tension. Perhaps, too, I simply enjoy taking myself back to the particular magic and intensity of that time of my life, when I left the city, found my home, and started on my writing career.

Promise, by Sarah Armstrong, published by Pan Macmillan, paperback, 400 pp, rrp $32.99

When a new family moves in next door, it takes Anna just two days to realise that something is very wrong. She can hear their five-year old daughter Charlie crying, then sees injuries on the little girl that she cannot ignore. Anna reports the family to police and community services, but no one comes to Charlie’s aid.

So when the girl turns up at her door asking for help, the only thing Anna can think to do is take her and run. Raising deeply felt questions about our responsibility for the children around us, Promise asks: if Charlie were my neighbour, what would I do?

For more information on Sarah and her writing go to: sarah-armstrong

The post Sarah Armstrong’s magical Mullum delivers her promise… appeared first on .

]]>The post Ireland, New York and Australia – the international world of poetry appeared first on .

]]>“Moved and amazed, I watched these patients who seemed almost catatonic in the home respond in strong emotional ways to the art,” she writes.

“They were utterly entranced and spent about 20 minutes staring at each painting.”

Laura’s poem was highly commended in the Gregory O’Donoghue International Poetry Competition held through the Munster Literary Centre in Cork, Ireland – munsterlit

A Little off the Top

The Barbershop, Edward Hopper, 1931, oil on canvas

Neuberger Museum, Purchase, NY

Enter from the lower left corner,

down the steps and into the shop

where the manicure girl waits,

thumbing her magazine.

We settle in, vintage voyeurs,

a long line of wheel chairs and walkers.

Follow the green curve of the ornate

brass railing, the white triangle of light,

sharp edge of window, a striped barber’s pole.

The docent asks, What does it make you feel?

Lonely, offers my mother. It’s the first

emotion I’ve heard from her in a decade.

Still, she adds. Nothing is moving.

And later, The girl is sad. She misses

her boyfriend.

Doris, gnarled hand

clutching a stuffed bear, says,

It feels cold.

Stanley, who I never knew could speak,

bobs his bald head and mumbles,

The man is hiding his face.

Published in the Irish, Southword Journal

Highly Commended in the Gregory O’Donoghue International Poetry Competition

The post Ireland, New York and Australia – the international world of poetry appeared first on .

]]>The post Just Write! Next courses start March 30 appeared first on .

]]>“This course is inspirational – it will change your life.” Cecilie Brown, Spain

Candida, who started Verandah Magazine 18 months ago, is the author of numerous books including the non-fiction series Yacker, Australian Writers Talk About Their Work; two novels, The Hidden and Women and Horses; a book of short stories, The Powerful Owl, numerous anthologies and several children’s books.

“I see my whole life as being creative,” says Candida. “I love to take photographs, and also to paint, and I’m also a natural horsemanship practitioner. I’ve found that if I can simply allow the creativty to flow then projects unfold in the most amazing way. I’m currently working on my third novel, based on the life of photographer Eadweard Muybridge, and I’m looking forward to sharing my creative process with participants in the course.”

As a journalist Candida has been editor of The Weekend Australian Magazine, deputy editor of the Good Weekend; arts editor of the Sydney Morning Herald and a feature writer on The Age. She was Director of the 2011 Byron Bay Writers’ Festival, and since then she has run numerous events and workshops in the Byron Bay region.

“Candida has worked with me for a year on my personal memoir, guiding me through the writing, editing and publishing processes. She’s been a great teacher – patient and inspirational. She’s helped me understand the difference between writing words and ‘being a writer’. I can highly recommend Candida – writers and would-be writers will truly benefit from her courses.” – Anna Middleton

“This is the Queen Bees Knees of writing courses – Candida really knows how to support people to achieve their creative goals.” India Morris, Lismore

To find out more about Candida Baker’s books go to: candidabaker.com/author

The post Just Write! Next courses start March 30 appeared first on .

]]>