The post A new book celebrates Australia’s writers appeared first on .

]]>I’ve been thinking about writing a lot recently. Even more, perhaps, than is usual for a writer. There’s a few reasons – the Byron Bay Writers’ Festival is fast approaching, I have a children’s book out in a month or so, and I’ve recently had an Eureka moment with a novel I’ve been working on for – I kid you not – ten years. And then, of course, there’s my online forum – Verandah Magazine, which often features interviews with writers, or reviews of local books.

It’s also 30 years ago that I started my three-book series, Yacker – Australian Writers Talk About Their Work, published by Picador over a ten-year period during which time I interviewed 36 writers. The books were a critical success, and in the process of writing them, I learned much about the craft of writing, and what makes writers tick. Even now, decades later, I often hear their voices in my head – the succinct summing up a particular writerly condition.

Glenda Adams spoke of the “outcrop of shale” that requires attention; Helen Garner of the need of reviewers to “grant the writers their material”; David Malouf of the fact that Australia tends to pigeon-hole their writers, that in Germany there is “one word for a writer – ‘Dichter’, and it simply means writer”.

For myself, what I’ve learned – and what I tell aspiring writers – is that at some point they will have to cross Mordor, the black volcanic plain in the Lord of Rings ruled over by Sauron, the chief Lieutenant of the first Dark Lord, Morgoth. I also think of this place we have to go to as ‘The Swamp of Despair’ in The Never Ending Story, where anyone who touches the dark water is imbued with a sense of such hopelessness they simply want to lie down and die.

In other words, writing is not always easy – and when it comes to surviving these dark phases, all a writer has is the torch of imagination, and a cape of creativity – both of which seem to go missing at regular intervals.

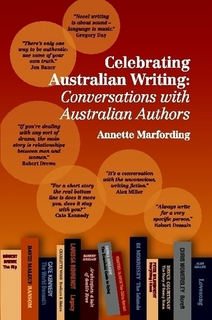

So all this said, it was with great pleasure that I recently launched a new book of interviews with Australian writers by Bellingen based Annette Marfording – Celebrating Australian Writing – Conversations with Australian Authors – who has interviewed 21 Australian writers about their writing and work habits.

Marfording, who has been the program director of the relatively new Bellingen Readers and Writers Festival, is also a broadcaster at Bellingen’s community radio station 2BBB FM. Originally from Germany, Marfording emigrated to Australia, studying and working as a lawyer. When she left her job as a legal academic and moved to Bellingen, it was initially in her role as a broadcaster that she began to be interested in the idea of collecting the interviews, and her interviewing talent combined with her passion for Australian writing makes this a deeply rewarding book.

In her introduction Marfording comments upon on what she believes is still wrong with Australia’s general attitude towards its writers, and specifically the inequities she believes are still at play. The space given to international writers in the press, for example, the tall poppy syndrome, the lack of attention given to small, independent presses, the amount of review space given to international authors in comparison to Australian writers, and so forth.

In the main of course, the writers themselves are not concerned so much with the level nature of the playing field, as with getting their work done, and all 21 one of them are eloquent on the subject of what is grist to their mill. With writers as diverse as David Malouf and Di Morrissey, or Robert Dessaix and Bryce Courtenay Marfording has chosen to talk to writers across the board, irrespective of perceived literary worth, and the book is the richer for it. Other writers include Cate Kennedy, Alex Miller, Georgia Blain and Michael Robotham – all varied voices on the subject of writing.

The brilliant Robert Dessaix talks about the ‘coup de foudre’ – the thunderbolt of almost falling in love with a creative project; Cate Kennedy talks about the almost oppositional feeling of detachment at the end of a book once it’s done and dusted; Charlotte Wood speaks eloquently on the nature of writing about violence and abuse, and there is a knock-out interview with novelist and legal academic Larissa Behrendt who talks openly about the auto-biographical elements in her books, and the continuing difficulties facing Indigenous writers today. Working in Indigenous affairs, her writing she says: “Saves me…without being too dramatic about it, it kind of saves my life.”

One of the most fascinating interviews in the book is the one with David Malouf, and Annette’s story about how nervous she was to approach him, and how happy he was to say yes. I loved it at many levels, not least of which was because it was so fascinating to read Malouf talking about his work 30 years after my interview with him in Yacker. In that time of course, he has won almost every major literary prize there is to be won, is translated into dozens of languages and has cemented his place as one of the world’s great writers.

Apparently the perceived wisdom these days is that books of interviews don’t sell. I hope that is not the case – both for Marfording and also for the Indigenous literary Foundation of Australia, to which she has donated any profits from sales.

These are important interviews. They provide – as I hope the Yacker series once did – a framework for their time, and a reference for future lovers of Australian literature to go back to and to learn from.

I hope that here in the Northern Rivers, and in the North Coast where Marfording lives, the culture of writing is flourishing strongly enough with our festivals and writers centres, and the staggering amount of writers of all kinds that live in these areas, for us to be able to prove that Australian writing is alive, well, and more than that, flourishing. Marfording’s book is an important one and I am sure it will go on to have a life in the cultural world of Australia for a long time to come.

Annette Marfording’s book: Celebrating Australian Writing – Conversations with Australian Authors is available from Lulu www.lulu.com you can contact Annette on [email protected]. The book will be on sale at the Byron Bay Writers’ Festival.

The post A new book celebrates Australia’s writers appeared first on .

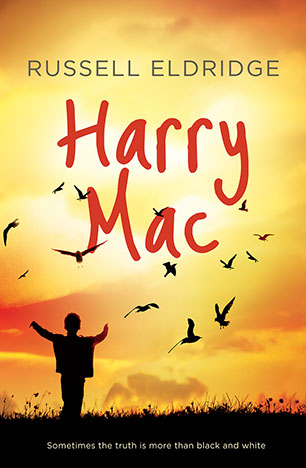

]]>The post Harry Mac – a novel of blood and ink, politics and the pen… appeared first on .

]]>Even if you had no idea that Russell Eldridge had ever been a newspaper man – there’s a dead giveaway, the moment you walk into his study. An absolutely utilitarian solid brown wooden desk, of the kind that populated the Fairfax and News Limited offices in the dim and distant pre-computer days.

“You’ve got it in one,” Eldridge says at my instantaneous guess. “It was the sports editor’s desk at the Sydney Morning Herald, and I was working at Fairfax when they were getting rid of them, so I put my hand up.”

The desk, which would have seen many thousands of stories cross its bows before it came into Eldridge’s possession, has certainly seen many since, but none quite as important to its owner has his most recent creation – his first novel, Harry Mac, which came about, he says, almost by accident.

“I’d retired as editor of the Northern Star,” he says, “and I’d actually written a crime novel. I was waiting to hear back from a publisher about it, and I was wondering what to write in the meantime, and suddenly the idea popped into my head. I think it had been sitting there in a little dark corner, but I’d never felt able to address it.”

The ‘it’ he is referring to his is childhood growing up in South Africa during the troubled years of apartheid, and Eldridge’s own experience of his father – the Harry Mac of the title, who was a newspaper editor and had been a POW in Italy during WWII.

“What I wanted to do was to try and distil the essence of those turbulent times,” he says. “When I was growing up in the fifties and sixties South Africa was a regimented society, a place which was still feeling the after-effects of World War II, and of the Boer War – there was the Secret Police, the Afrikaner Boers with their Dutch background, some of the Germans that were still on the side of the Nazis, and those of us from an English background who were caught in this middle-ground – seeing the oppression of the black population and at the same time living very comfortable lives that many of them did not want disturbed.”

The central element of the plot is that young Tom, Harry Mac’s son, overhears his father being told of a political assassination plot, and becomes terrified to think that his father is going to be caught up in what Tom is already sensing is a net of trouble closing in around not just his neighbourhood but the larger world outside.

For Eldridge, the plot was the pivot around which the rest of the book could grow. “It was actually based around the fact that our father had told us about a plot, but he’d dismissed it, but I began to think how that could play out as a fictional story, and that this was also around the time that Mandela was about to be arrested – he even hid in a house in our grandparents’ street at one point – and suddenly everything started to come together.”

It was the idea of how a child might have felt if he had imagined that his father was involved in something dark and dangerous that prompted Eldridge to use a child narrator. “It was liberating to use a child’s voice,” he says. “It allowed me to write about complicated things in a straight-forward way, with no adult baggage or cynicism attached. Of course, I had to pay a lot of attention to keeping up the child’s voice – not allow it to slip into using a more complicated vocabulary and at the same time keep it from being too childish.”

But young Tom has a way with words and a quiet observational skill – not unlike his creator. Working at the Northern Star with Eldridge when he was editor was a pleasure, although he says, he was not really cut out to be editor material.

“I moved to Australia in 1979,” he says. “My older brother had already moved to Australia, and my then wife and I were living near Soweto – close to the middle of the trouble spot for the riots, and I really felt it was time to get out. When we arrived I worked on the Sydney Morning Herald for a few years, and then I discovered the North Coast, and came up here to be a hippy in the hills which was good fun for a couple of years, but I gradually got sucked back into journalism, first of all working as a reporter and then as chief of staff.”

Eldridge was not, he says, automatic Northern Star editor material. “The Star was terribly conservative back in the day,” he says, “I really didn’t fit the bill. I was chief of staff for ten years before I was offered the editorship.” He found working on a local newspaper a rewarding experience. “It has its challenges,” he says. “You feel accountable to the people around you in a way that you don’t when you are working on big city newspapers, and of course it can often test your independence as a journalist.”

Something Eldridge took to heart however, was the importance of belonging to community, and for those of you who haven’t seen him act, he is a fine actor, as well as an active member of the Byron Bay Writers’ Festival Committee, and over the years he has immersed himself in many causes dear to his heart.

Some of the tests of independence Eldridge gives to Harry Mac as he struggles to make sense of the increasingly rigid regime bearing down on them – his mood swings and drinking affecting the Mac family, in particular Tom’s Mum, who treads around her volatile husband cautiously, trying – usually unsuccessfully – to prevent an outburst, or worse, a silent treatment that goes on for weeks.

‘I can’t help feeling the lane where we lived had something to do with it all. As though these families had been put there for a reason… it was so still, like everyone was holding their breath a lot of the time.’

Tom, however has an outlet for his worries – the lane in which he lives, which is populated with a cast of colourful characters, and most specifically his friendship with Millie, a girl slightly older than him. Tom and Millie have a bond – both of them are slightly physically disabled, Tom from the after-effects of polio, and Millie, whose neck is shortened. “I don’t know if Millie’s mother took thalidomide,” Eldridge says, “but I wanted to point to that time as being the peak era for thalidomide and polio, and how children with a physical disability were commonplace – and to create a connection between the idea of these damaged children, and the damaged system in which they were living. For me a central part of the book is the idea of ‘bearing witness’. That is that perhaps as a journalist or writer you are not always on the frontline, but it’s your job to observe and report – and I wanted to bear witness, not just to the dark politics of the day, but also to other, more personal issues.”

There was too, a personal connection with the idea of disability, since Eldridge has suffered on-going after-effects in one leg of an inherited condition similar to polio, although he has not let it stop him from climbing, even including hiking into the foothills of the Himalyas. At the house in Ocean Shores where he lives with his wife Brenda Shero, an artist, designer and writer, the couple have a kayak Eldridge frequently takes on the river, and it’s often, he says, when he’s out on the water that the next step in his writing will come to him.

Which leads me of course to the inevitable question of what he’s working on next. “To be honest the tank feels a bit empty at the moment,” he says, “but what I am very heartened by is the response from a lot of people who are saying they don’t want to let go of the characters – they want to re-visit them.”

In the mean time, of course, there’s always that crime novel sitting in the drawer.

Marele Day will launch Russell Eldridge’s book, Harry Mac at the Launch Pad at the BBWF on Saturday August 8 at 3.00pm. For more information on the Festival go to www.byronbaywritersfestival.com

Harry Mac is published by Allen & Unwin: https://www.allenandunwin.com/browse/books/fiction/Harry-Mac-Russell-Eldridge-9781760113209

The post Harry Mac – a novel of blood and ink, politics and the pen… appeared first on .

]]>The post The writer, the filmmaker, the taxi and the poem… appeared first on .

]]>Irish novelist Evelyn Conlon ponders the power of memory, friendship and synchronicity as she recalls old landscapes from 1973 and new friendships made in Byron Bay.

Imagination is a great emotion, on a par with memory for one of the best free things in life. We know that the second best can be wildly expensive so it behoves us to wallow in the enjoyment of the firsts, when we can remember to do so. It is the combination of both of those things that allows me to write to Bryon Bay from a brisk Dublin day, now stitching its hem up gradually into earlier nights.

I first went to Byron Bay on my way to Brisbane in the early 1970s. I had arrived off a ship like so many before me, in time to be there the night Whitlam was elected. After six months I had now left the large city of Sydney and was wandering northwards in a kitted out Kombi Van, journeying around Australia, or at least a bit of it. This was not as common as we might think, and in those days it still gave rise to suspicious looks in places. I was a passenger in the van, not the driver. But I did hold the old AA strip map and so had control over where we might stop of an evening. As a fiction writer I should lie to you now and tell you that I remember exactly what the place looked like but in truth I don’t. It melded into a group of stunningly beautiful, breathtaking experiences that I was having on that journey. When I dream of it I dream a turn in a long straight road that then brazenly opens out into an aquamarine blast to the eyes.

That’s the picture I had when I got the invitation to read at the 2011 Byron Bay Writers’ Festival (from the publisher of this magazine) all those years later. And I have to admit that I went to look for that bend in the road but couldn’t seem to find it. Never mind, there might be another time. What is astonishing, now that history has had its way, is that I never heard of the Aquarius festival of 1973 and surely we were passing through about then. Gosh if I had, who knows whether Rathmines, Dublin, would ever have become my home?

I was a bit floored by all these memories on my visit there in 2011, and a bit distracted by them, I think, when I got into the shared taxi to the reading venue with a man who was swallowing tablets. He said he needed to take them on time, otherwise he could be in serious trouble and I said that he’d better get on with it because we didn’t want a dead passenger. I was reared in a house surrounded by a clatter of nurses so I can sound deeply unsympathetic to medical emergencies, even when that is not my intention. I was also wallowing a bit in the joy of the previous night with a houseful of visiting staunch readers, women from all over Australia, come together in a rented house for the festival.

The man turned out to be Paul Cox, filmmaker extraordinaire, and he was on his way to speak at a roundtable discussion about trauma – in his case that of having a liver transplant. There really was a need for him to be taking his tablets on time. I was interested because my own sister was on the list, as those of us who know this parlance call it. (There’s another list in this house, it’s the one to get a flute made by Chris Wilkes and we can talk of that lightly, now that my sister has had her operation and, like Paul Cox, has been given another run at life.)

Paul and I had a great half hour in the green tent before we went to our different tables. I had to do a dash to the airport afterwards, having forgotten to get the man’s full name and address and forgotten to give him mine. But, as is sometimes the way of things, particularly things that happen in spots like Byron Bay, we found each other again. Some months later Paul Cox was speaking to his partner Rosie, or I Gusti Ayu Rus Astini Raka to give Rosie her full name. He’d left a poem out for her – one by Norman MacCaig that I had given him before running to our tables, and he’d mentioned my name. In the library, Rosie took down a purple book, because she loves the colour, and lo and behold it was one by me. We definitely had to be in touch. We’ve been friends since.

Byron Bay is I hope a place I’ll see again. But in the meantime as I sit here, carefully watching a quiet bird – no relation of any of your noisy Australian birds – I can marry imagination and memory and come up with a lovely picture altogether, which will do just as well for the moment.

Evelyn Conlon

The post The writer, the filmmaker, the taxi and the poem… appeared first on .

]]>The post Winterson’s World appeared first on .

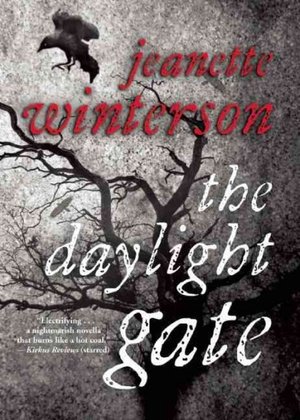

]]>

Jeanette Winterson: keynote speaker at this year’s 2014 Byron Bay Writers’ Festival. (Photo: David Levene, The Guardian.)

Never one to shy from controversy, Jeanette Winterson’s appearances at this year’s 2014 Byron Bay Writers’ Festival are likely to be feisty affairs, writes Digby Hildreth of the Festival’s keynote speaker.

British author Jeanette Winterson’s contribution to this weekend’s Byron Bay Writers Festival is guaranteed to be thought-provoking – and possibly provocative in other ways.

Most recently, the festival’s keynote speaker was engaged in a Twitter scrap for killing and eating a rabbit that was chomping on her parsley and roses.

She started the row by posting grisly photographs of the deceased bunny as she prepared it for the oven – anathema to some of her more politically correct admirers.

One tweeted: “You make me sick. I will never again read a word you write. Rest in peace, little rabbit.”

The heated Aga saga may have lost her a few readers but it also revealed Winterson in her true, and best, light: brave, funny, ruthlessly honest, challenging cant and wimpishness.

“Why is farmed meat fine but personally trapped disgusting? Think about it,” she retorted to the squeamish former fans.

Food and the politics around it are high up on Winterson’s list of concerns: she has even opened an outlet for organic products in East London. But she is better known for her consistently profound and insightful studies of queer and gender politics, body image, adoption and, most recently, witchcraft.

Her first novel, 1985’s Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit daringly told her own story in fictional form – how she survived an appalling adoptive childhood, marked by deprivation, abuse and extremist Christianity to emerge in her early teens as a lesbian.

Resisting the label autobiography she noted that when male authors pulled the same trick it was hailed as “meta-fiction”. The novel contained a passionate personal manifesto: “I want someone who is fierce and will love me until death and knows that love is as strong as death, and be on my side forever and ever. I want someone who will destroy and be destroyed by me.”

Winterson was born in Manchester and grew up in nearby Accrington, in the North “the dark place”, “untamed” – qualities which could be attributed to the writer and much of her work.

Her most recent fiction, The Daylight Gate, is a study of the horrors of 17th century witch trials in Lancashire – really a convenient excuse to persecute Catholics. It spills over with blood, torture, cruelty … every type of human vileness, redeemed somewhat by courageous characters who know that, once again, “love is as strong as death”.

There is a nine-year-old girl in it, starved, raped, half wild and half mad, who could be an echo of Winterson herself, as revealed in her autobiography, Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal? (the title is a quote from her mother, responding to Winterson’s coming out as a lesbian). Forced to sleep outside at night, or in the coal cellar, Winterson grew up tough, resilient, and damaged.

Adoption, she writes, made it “impossible to believe that anyone loves you for yourself”.

She survived it through literature, reading and memorizing poetry: “A tough life needs a tough language – and that is what poetry is.”

When her mother burns her books, it marks a breakthrough.

Standing amid the smouldering paper, she thinks: “Fuck it, I can write my own.”

Winterson is giving the Keynote speech at 11.00am on Friday August 1, and she will discuss ‘Creativity and Craziness’ with Susie Orback at the Byron Bay Writers’ Festival on Sunday August 3 at 2pm.

Digby Hildreth

The post Winterson’s World appeared first on .

]]>