Burundi may be the unhappiest place on earth, but it’s still got a nerve when it comes to scamming, writes Robert Drewe.

Three times this week my household has been woken at two a.m. by phone calls from Burundi. We’ve never been to Burundi. Nor do we know anyone from Burundi. To be honest — and I hope Burundians don’t take this the wrong way — I’m determined never to step foot there.

It’s not just being woken up three times at two a.m. by Burundian callers, who then swiftly hang up, that has influenced my decision not to visit Burundi. The Department of Foreign Affairs doesn’t want me — or any other Australians — to go to Burundi. They not only strongly warn against it, they say that if I’m in Burundi already to get the hell out.

Why? My Burundi knowledge was sketchy, limited to grim news reports of 300,00 Tutsis and Hutus slaughtering each other there and in neighbouring Rwanda in the 90s. So eventually I did what anyone does when Burundi phones them three times a week in the middle of the night: I Googled Burundi.

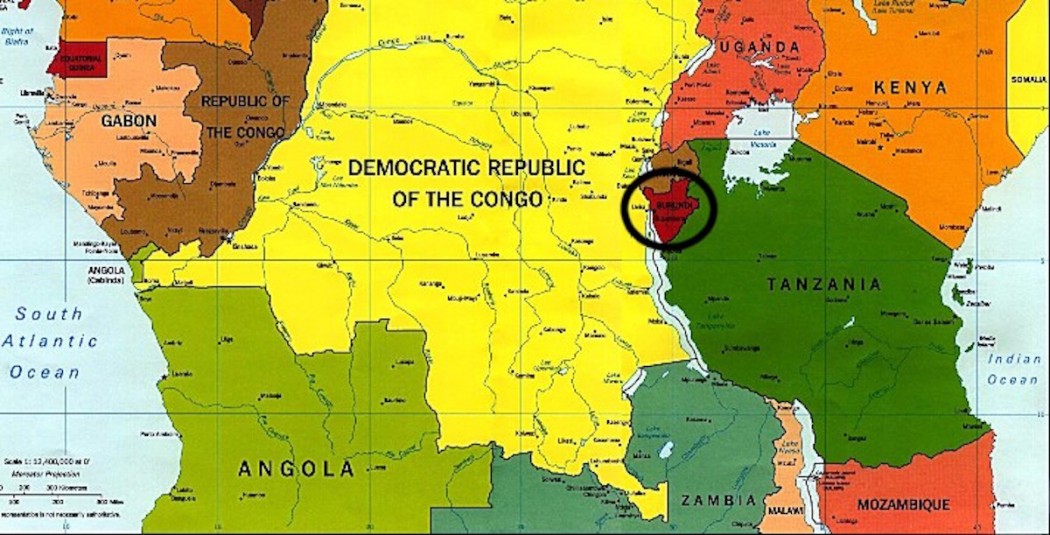

The news wasn’t favourable. The former German and then Belgian colony is a landlocked country in Central Africa, one of the world’s poorest and most violent nations, struggling to emerge from 50-years of ethnic-based civil war, ongoing conflict with Rwanda, assassinations and genocide.

It’s also beset by widespread disease (yellow fever, malaria, HIV/Aids, cholera, filariasis, plague, sleeping sickness, meningococcal, TB and — for anyone attempting to swim in Lake Tanganyika — schistosomiasis). Also malnutrition, banditry, Al Shabaab terrorists, armed rebels, carjackings, kidnappings, drought, floods, landslides, landmines, road blocks, over-population and almost complete de-forestation. Think of something really bad, anything at all, and Burundi’s got it.

Anything pleasant to offset this dire state of affairs? Well, without the unspeakably brave ministrations of Doctors Without Borders, and foreign aid, which provides nearly half the nation’s income, average life expectancy would doubtless be lower than the present 50 for both sexes.

On a United Nations index called the World Happiness Report, which considers such variables as real GDP per capita, social support, health, life expectancy, personal freedom, and perceptions of corruption, Burundi comes equal last (154th) – the equal unhappiest country on earth — with its neighbour, the Central African Republic.

Even beleaguered, war-torn Iraq (117th), Afghanistan (141st) and Syria (152nd) are happier places than Burundi. (By way of contrast, Norway comes first in happiness and, counting one’s blessings, Australia is ninth. America is 14th and Britain 19th.)

The Burundi media is heavily censored and any criticism is regarded as treason. You can’t go for a jog in Bujumbura, the capital, unless you register with the government and join a jogging club. Then you must jog in one of nine approved venues. The police may have some questions about your jogging: “How many people will be jogging with you? At what time? Give us their names.”

In their dire circumstances, perhaps you can’t blame the Burundians for talking a leaf out of Nigeria’s infamous book and joining the scamming industry. Because that’s what their dead-of-night international phone calls are about.

The scam, originating in Japan, is called Wangiri, meaning “one ring and cut”. Mostly you receive a call deliberately in the middle of the night when the recipient is disoriented: the phone gives a single ring or two before the caller disconnects.

The scammer will have hired an international premium rate number (IPRN) from a local phone company. The trick is to get you to call back on the same premium-rate number. You’re probably thinking you missed an important call (from overseas — it must be important!). When you call back the unfamiliar foreign number (Burundi’s prefix is +257) your call is taken but the person on the line doesn’t talk to you.

You’re sitting there in your pyjamas, blinking at your mobile, saying, “Hello, hello, hello, is anybody there?“ Eventually, receiving no answer, you get frustrated and hang up. By then you’ve lost quite a bit of money. You’ve been charged higher than regular calling rates, and the revenue earned is then shared between the telecom operator and the owner of the number from Burundi. Or maybe from Malawi (+265), Nigeria (+234), Tunisia (+216), Russia (+7), Belarus (+375) or Pakistan (+92).

According to Scamwatch, run by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), 155,035 Australians were scammed — by all methods — of $83,563,599 last year.

The biggest losers, mostly males, lost $32,278,469 to jobs and investment scams. The second biggest losers lost $25,480,351 to dating and romance scammers. The victims were mainly (presumably lonely) 55 to 64-year-old women.

Maybe we’re finally waking up to the dreaded Nigerian scammers. They only made $1,404,108 out of gullible Australians in 2016. No figures were available on the Burundians. But we didn’t call them back.

Robert Drewe’s latest novel, Whipbird is out now: penguin.com.au.whipbird