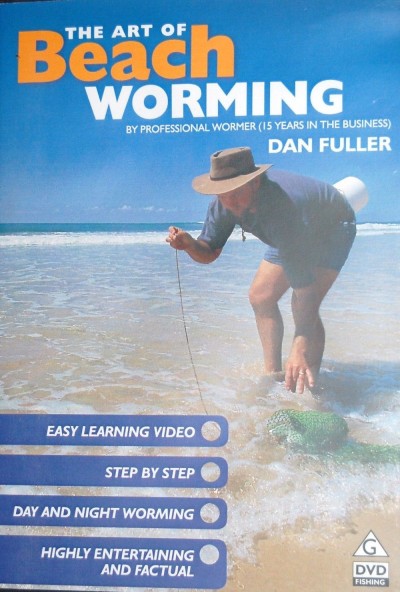

Robert Drewe finds that there’s more than meets the eye to being a beach-wormer – including, he suggests, a bit too much buttock cleavage…

Once observed, they’re pretty unforgettable: stringy red creatures usually between twenty centimetres and a metre in length, with whiskery legs, like an elongated centipede, they can grow to three metres.

They’re called polychaetes. They live under the sand in the shallowest water of the smooth, flat shoreline around here, and eat dead and decaying sea-life. They’re slimy, shy, segmented, strong-jawed and very strong, and fish, especially bream, whiting, mulloway and flathead, love to eat them when they get the chance. Consequently, on this coast they’re in great demand as bait and have given rise to one of the oddest and most difficult occupations in the country: the beach-wormer.

As someone professionally interested in Australia’s version of homo sapiens, I find beach-wormers an intriguing off-shoot of the common-or-garden coastal dweller. They all seem to be men over sixty for a start, with a uniform physique.

I’ve never seen a young beach-wormer. Or a tall one, or a skinny one, though I did see a female wormer once. Of necessity, wormers have a low centre of gravity, with knees surprisingly close to the ground, widely splayed toes, and calves like clenched fists. They wear their shorts well below their impressive stomachs (which perhaps aid balance), exposing buttock cleavage that lengthens alarmingly as they bend and sway surprisingly nimbly over ankle-deep water on the tidal sand flats. A dodgy lower back will end a wormer’s career.

They take their work seriously and silently. The constant bending over, the effort involved, and their age, combine with sun and wind to give the typical wormer a ruddy, almost purple glow. Facial veins and eyes swell and strain. A wormer has to stay patient and alert at all times, his reflexes snappy, so you rarely see one who isn’t frowning.

So swift and elusive are beach-worms that even though thousands of them lurk just beneath the sand on any New South Wales beach it might take two or three years of training and observation before a new wormer actually pulls up his first worm. For amateur wormers the official bag limit is twenty worms a day, but they’re by no means endangered and commercial wormers, who are licensed, may take more.

That a whole secret stratum of hungry beach-worms with carnivorous mouths lives inches under your bare soles is a rather creepy thought as you wade out into the surf. Little is known about them: whether they live only on the shore, whether they always lie flush with the surface or burrow deep. Their sex lives is a mystery but their large numbers indicate that reproduction presents no difficulties: their sex organs make up the middle third of their entire length.

So how does a wormer conduct his delicate craft? He carries an old nylon stocking containing rotten meat and oily pilchards in one hand and a pair of worming pliers in the other. (As a backup, he anchors a second smelly bait-supply in the sand with a stick.) Then he gently waves the lumpy, smelly stocking back and forth over the receding wavelets. If he’s lucky a worm will pop its head up, its V-shaped mouth breaking the surface, to see where the tasty stink is coming from.

The wormer then bends over the worm’s head with a tidbit of rotting fish in his fingers. He’s coaxing the worm into tasting it. As its mouth bites the bait, he fits the jaws of the pliers gently around the worm’s head and hopes that its hunger will counter its shyness and lightning-fast movements.

Seconds pass. He mustn’t scare it away. The wormer is bending over for so long his eyes seem ready to pop out. A seizure looks imminent. Abruptly he closes the pliers’ grip, deftly flicks the worm out of the sand, and runs a quick gnarled hand down its length to remove its slime. He has it. The worm is in the bag.