Traveling in France, Candida Baker ticked an item off her ‘bucket list’, when she visited the Lascaux Caves…

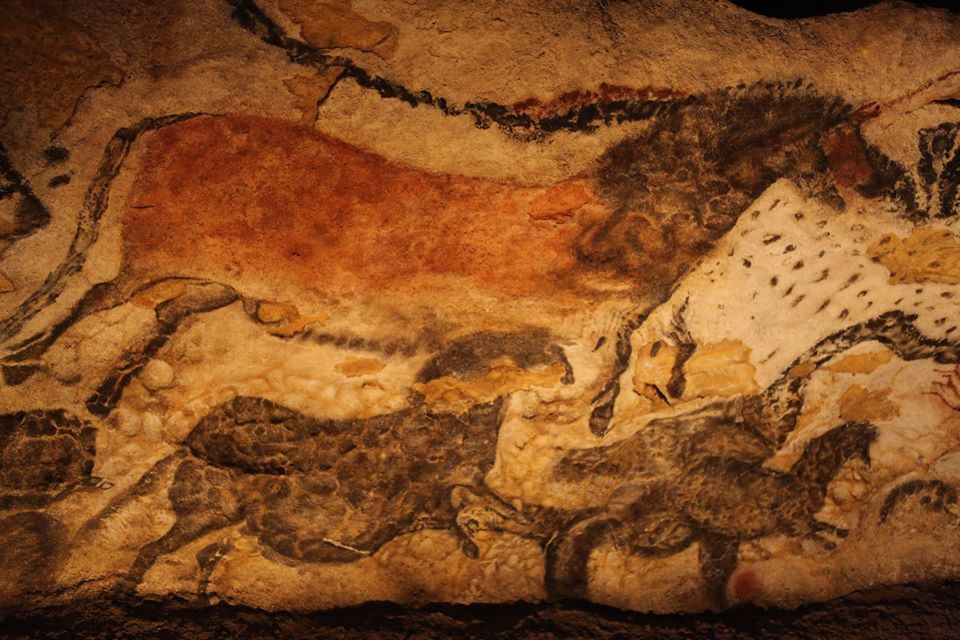

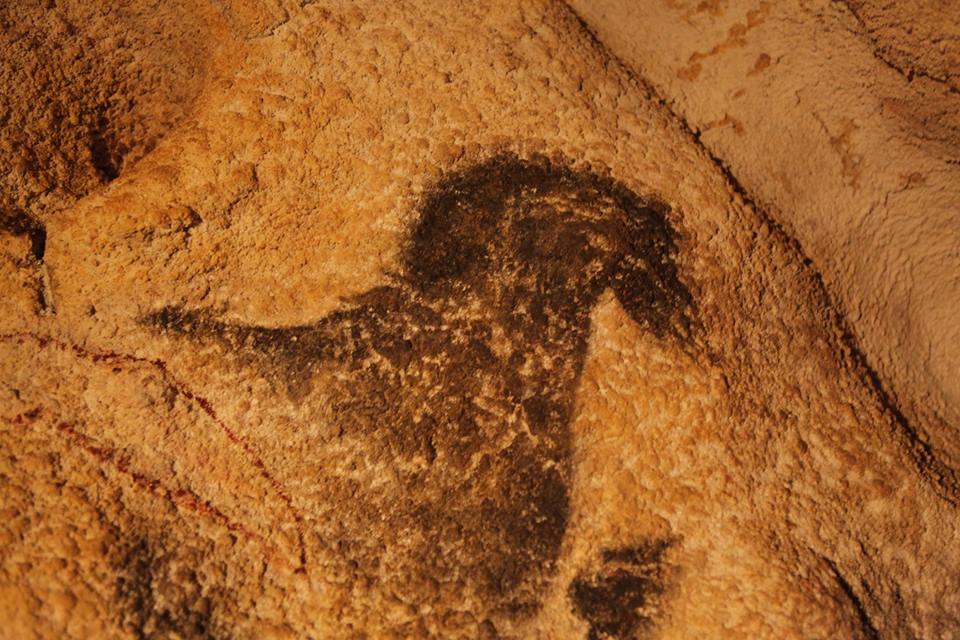

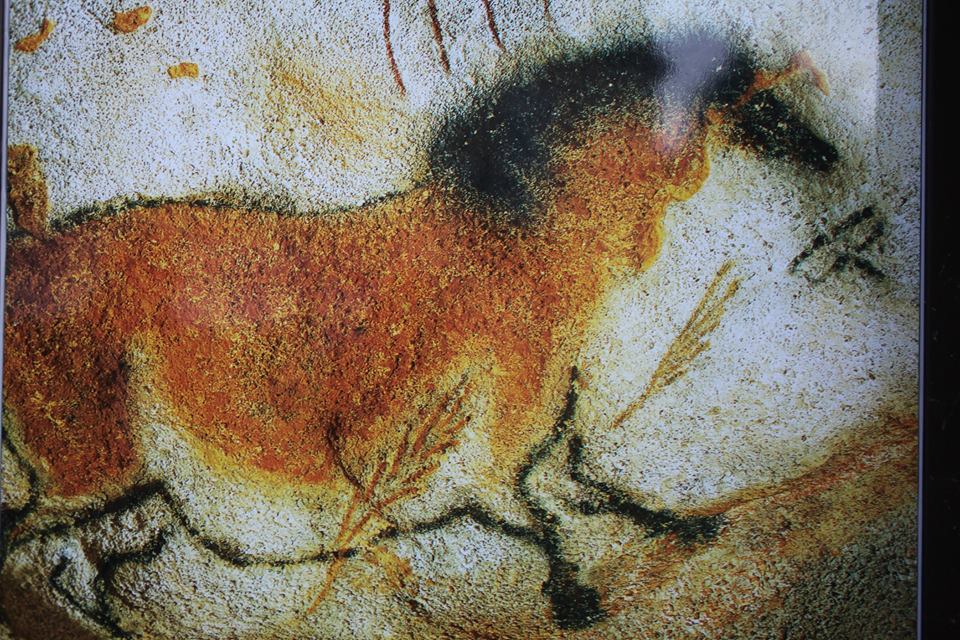

After a month in France in September, my very last ‘horse’ adventure was at the ancient Lascaux Caves in Montignac. I’d seen these magical caves on endless documentaries, and I’d always wanted to see them in person – and to continue learning about the relationship between horses and humans. The cave paintings – and you will have all seen the images I’m sure – are from 17-20,000 years ago, and feature a wide variety of animals that are recognisable today – including aurochs, bison, reindeer and horses – lots and lots of horses!

The caves (other than one original at Rouffignac which you visit in a train, passing ancient bear nests on the way) are exact copies of the originals and in the case of Lascaux 2, which was the one we chose to visit, only 100 metres from the real cave’s entrance. The caves had to be copied because unfortunately the amount of people going through them once they were discovered caused almost immediate damage to the paintings. The copy itself took seven years to complete, and the sites are incorporated into the World Heritage list.

.I can’t even begin to describe the feeling of being surrounded by these wonderful images of horses – and the energy in the paintings. But THEN – even better, we visited a wild-life park nearby where they have a Przewalski’s horse – or Dzungarian horse, a rare and endangered subspecies of wild horse (Equus ferus) native to the steppes of central Asia.

It was extinct in the wild but thanks to a careful breeding program it has no been reintroduced to Mongolia. Most “wild” horses today, such as the American mustang or our own https://www.viagrabelgiquefr.com/ brumby, are actually feral horses descended from domesticated animals that escaped and adapted to life in the wild.

The Przewalski’s horse has never been domesticated and remains the only true wild horse in the world today. The horse is named after the Russo-Polish geographer and explorer Nikolay Przhevalsky (Polish name: Nikołaj Przewalski) and I’ll let you be the judge of how similar the little chap (who has donkeys for company at the moment) looks to the ancient cave paintings.

The grey ponies also tell a wonderful story because the Tarpan – also known as the Eurasian wild horse or simply, wild horse, is now extinct. The last mare believed to be of this subspecies died in captivity in Russia in 1909, but in the 1930s, several attempts were made to develop horses that looked like tarpans through selective breeding, called “breeding back”. Historians of the ancient wild horse assert that the word “tarpan” only describes the true wild horse but at the same time, the breeding program has been successful enough to produce these lovely grey ponies that bear a very distinct resemblance to their ancient ancestors.

So what I did glean from seeing the Camargue horses, the Cardre Noir dressage horses, and the ancient cave drawings? It yet again reinforced for me how the relationship between horse and humans is one of – when it’s good – a chosen relationship, on both parts. Finally, if you do happen to have an interest in horse history I can highly recommend Susanna Forrest’s The Age of the Horse which I reviewed for the Times Literary Supplement in the UK. It’s a fascinating account of the history of the horse from around the world. https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/public/horses-tale/