Did you know that the male echidna has a four-headed penis? Or that the female echidna has two vaginas? No? Well neither did Robert Drewe until he went in search of stories about the prickly little fellow making holes in his lawn…

The mystery of the neat holes in our lawn every morning has been solved: we have a resident echidna. He or she (with an echidna who can tell?) makes the holes with his/her beak while hunting ants, termites and worms. It’s amusing to watch Spike trundling importantly around the garden, like a cartoon character on a mission.

Echidnas are my favourite Australian native animal, and Spike (an original name, eh?) appropriately came along just when I was asked to give a talk on a subject new to me, Animals in Literature. Aha, here’s my lead, I thought. Well, I looked up Echidnas in Literature and despite their popularity in kids’ books, as lolly logos, and on coins, I couldn’t find them anywhere. All I found of a literary nature was the following reference, from Greek mythology:

“Echidna was a monstrous she-dragon, with the head and breast of a woman, who presided over all the corruptions of the earth: rot, slime, poison, fetid waters, illness and disease, and who spawned a host of terrible monsters to plague the earth.”

A bit harsh, I thought, watching roly-poly Spike nuzzling his/her way into an ant nest. Was the British naturalist George Shaw, who first described echidnas in 1792, thrown by their uniqueness? It’s unlikely that George was aware of the males’ four-headed penises and the females’ two vaginas, because echidnas are notoriously shy. Captive breeding is unknown, even in the libidinous 21st century. They hate to be observed while mating, and in the circumstances who can blame them?

Anyway, George was possibly not the man for the job, having already failed to conceal his scepticism when confronted with a platypus (the echidna’s monotreme cousin) and concluding that the specimen was a fake.

For my talk, echidnas, sadly, were out. I cast my mind back to the first animals to thrill me in books, and Rikki-Tikki-Tavi, the valiant young mongoose in Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book, sprang to mind. This story was read to us by Miss Dunkley in Grade One, and I must say its plot still lingers, chiefly in my concern about venomous snakes entering the house (again).

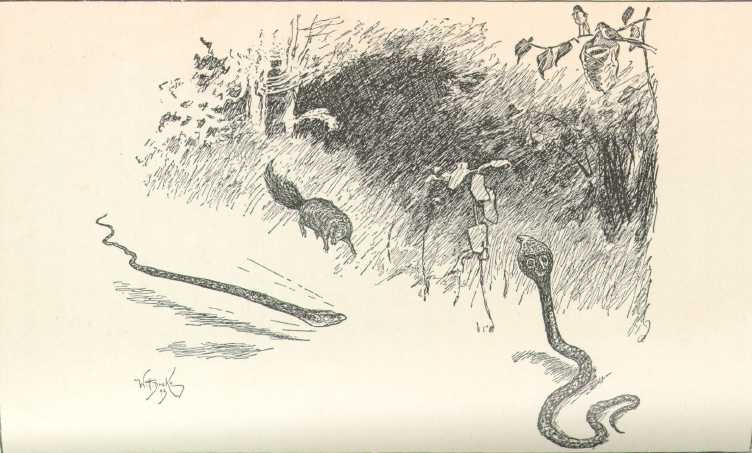

The story follows the adventures of Rikki-Tikki-Tavi, the pet of a British family in India. Other animals in the family’s garden warn Rikki of the presence of two cobras, Nag and Nagaina, who are furious at the family invading their territory.

Nag enters their bathroom before dawn but is attacked by Rikki. Their struggle wakes everyone and the father kills Nag with a shotgun. So Nagaina attempts revenge, cornering the family as they eat breakfast on the verandah. While Nagaina is distracted by a tailor-bird, Rikki destroys the cobra’s brood of eggs, except for one. He carries the egg to where Nagaina is threatening to bite the little boy, Teddy. Nagaina, enraged, recovers her egg, but is pursued by Rikki to the cobra’s nest where a final battle takes place. Rikki emerges triumphant. Nagaina is dead.

Phew! An environmentally-incorrect verandah breakfast these days (“Look dear, there’s another nice cobra! An even bigger one. Yes, it’s his house, too. Eat up your huevos rancheros”). But powerful stuff when you’re six.

Animals feature prominently in children’s books, where sentimentality is given free rein (think Black Beauty, The Yearling, The Chronicles of Narnia) and where moral questions can be safely planted in young minds by making the animals think and act like people.

From books to films C. S. Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia have thrilled generations of children with his stories of talking animals.

From Aesop’s Fables to Animal Farm, animals have brought many a philosophical and political message to adult novels (White Fang, Call of the Wild, Watership Down, Jonathan Livingstone Seagull, Life of Pi, Maus), and to poetry, from T.S. Eliot (Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats, which as the musical Cats, brought Eliot’s publisher, Faber, more money than any poet ever has) to Ted Hughes’ many wildlife poems. And to The Island of Dr Moreau, where H.G. Welles had his character Dr Moreau create human-like beings from animals via vivisection, and dealt suspensefully with a number of philosophical themes still current, including pain, cruelty and human interference with nature.

Nowadays while we’re talking about animals we have to consider a subject that didn’t even occur to the omniscient Welles: global warming. When it comes to ecological footprints, a dog is allegedly the equivalent of two Toyota LandCruisers, and this includes both the manufacture and running of the car. There are more than three million Australian households with at least one dog. That’s a lot of LandCruisers.

Dogs can’t take all the blame – a cat is the equivalent of a Volkswagen Golf. And a guinea pig has the same carbon footprint as a plasma television. As my old Dad used to say, you wouldn’t read about it.

Robert Drewe’s latest book, The Beach, an Australian Passion, has just been published by the National Library of Australia and is available here: the-beach-an-australian-passion His other recent books The Local Wildlife and Swimming to the Moon are on sale here: penguin.com.au

…