The Bentley blockade camp, which lasted nearly three months, was vindicated on May 15, 2014, when certain technicalities, conveniently brought to light under immense pressure from community resistance, lobbying and some peculiarly acute political conditions, culminated in an announcement that Metgasco’s bid to drill for gas in Bentley had been foiled. Almost soon as the tents and the tripods started to come down and people began to figure out how to extract several tonnes of vehicle and associated implements embedded in concrete, the blockade near Casino in northern New South Wales was already being analysed and dissected by journalists, academics, police, politicians, conspiracy theorists, the Mining Council and think tanks across the nation, writes Mick Daley.

On Sunday, May 18, 1014, Greens Senator Larissa Waters declared to the gathered protectors around the Bentley blockade campfire: “We are going to take our country back.”

It was a prescient moment and it came only hours before NSW Energy Minister Anthony Roberts announced that gas mining company Metgasco’s bid to drill in Bentley had finally been foiled.

Up to 1000 riot police had been booked to come in on May 19 to break up the camp – projected to have been filled with at least 7,000 people, on what I’m calling for convenience ‘B’ day – in an action that it now seems was prepared for casualties, even deaths.

The conclusive victory saw a speculative mining company brought undone, a deeply compromised State government stopped in its tracks and a police force tentatively align itself with a community based mass movement. In fact the Bentley victory has been described as a counter-reaction to a purpose-built economic attack on a nation – a democratic uprising against the agendas indelibly inscribed in the last Budget.

Western Australian Greens Senator Scott Ludlum, visiting the camp with fellow Greens Larissa Waters and Jeremy Buckingham, made precisely this observation after a dawn vigil and breakfast on Sunday May 18 – the day before ‘B’ Day. “What you’ve done up here is immensely and profoundly important,” said Ludlum. “Industry reached a tentacle out, it touched the ground here, and you bloody well chopped it off.”

Amidst loud and sustained cheering, he inserted a cautionary note. “The stories told of the Franklin, of Jabiluka, they’re going to be told of Bentley and the reason those stories are told is that we really need to know how you did it, because this is a climate emergency,” Ludlum told the crowd. “Linking arms with other countries around the world is the most important thing we can do now.”

There are as many different interpretations of events as there were people at the blockade, but there were some factors undeniably essential in framing the minister’s final decision to thwart Metgasco. The assertion of our indigenous peoples’ power and dignity, as they positioned themselves at the heart of this movement, gave it a gravitational focus, momentum and purpose that has immeasurably enriched all involved. A sophisticated electronic and social media campaign, orchestrated by dedicated volunteers, spread the news of the blockade virally and made it an international rallying point for climate change and anti-gas mining advocates.

Fund-raising and public awareness campaigns spawned spontaneous and highly orchestrated events and concerts that attracted eminent performers and public figures to stand as popular figureheads of the movement. The timely juggernaut of ICAC’s investigations into political donations opened up a black hole so potent that it’s already sucked nine LNP MPs, including former Premier Barry O’Farrell, into disgrace and political limbo. In this dangerous political climate Metgasco themselves were ensnared, as Energy Minister Anthony Roberts nimbly intercepted ICAC’s lethal trajectory, drawing a line between their chief shareholders – a company compromised by its toxic connections to Australian Water Holdings, the corporation at the heart of the Eddie Obeid dynasty.

As well, the effect of Alan Jones’ radio broadside cannot be underestimated. Though his personal narrative and political views are largely abhorred by left-leaning constituents of the anti-gasfields alliance, there is no denying that his personal feud with the industry and his own incipient political influence were mighty, if unlikely allies in this campaign. His interviews with anti-gas activists, last minute announcement of the costs of the impending police campaign, projected at $14 million, and his personal intercedence with State ministers proved crucial in getting the message across that this was a mainstream concern.

But Annie Kia of Lock the Gate is emphatic that while the inexorable growth of an aligned social movement was instrumental in this decision, a last minute tactical intervention helped turn the tide.

“The political campaign that ramped up in that last fortnight from the Gasfield Free Northern Rivers advocates and from the landowners from Bentley was vital,” Kia noted.

“We made available to government a very specific brief that outlined the deception involved in Metgasco’s statement in blow by blow detail – that they had specifically characterised it as a conventional well, when in fact in other places they had made it clear that they were seeking tight sands gas potential. I think that was a significant thing and…there was unbearable pressure on the government during that last week.”

The police force itself displayed a distinct reluctance to be that wave of storm-troops that the industry demanded. Quelling a genuine spontaneous community uprising with violence proved not to their taste, as events proved.

Aidan Ricketts, the veteran activist and academic whose work on social movements has been instrumental in framing the Gasfields Free Northern Rivers community strategies, had this analysis of the police response. “I think we achieved something very significant where the police look at themselves and say, ‘we don’t want to do this, this is our people’,” he says. “I think that’s one of the most amazing things hiding in the background of the Bentley story, because of course the police don’t want to come out and say it explicitly, but they were very reluctant. There was a little bit of subtle resistance in that they were saying ‘ok we need 900 police for eight weeks because that’s how long the drilling goes and we know this community isn’t going to back off and they’re going to stay in hotels and it’s going to cost you’ – the basic figure was $10 million and there was no assurance it was going to stay within that. I know from our meetings with the police they were very clear that they would have preferred a political solution and they were very relieved when there was one, they phoned us straight away and congratulated us.”

The community representation at all levels was absolutely vital – from Simmos (arrestable volunteers) camping throughout all weathers and threats to the work of lobbyists in Sydney – all adding weight to the tipping point.

“As soon as the police went away there would have been 3,000 people sitting on the rig and that could have happened as many times as was required, at ever spiralling cost to the State Government,” says Ricketts.

He points out that what happened at Bentley is in many ways unique: “It remains an amazing story because there’s no historical precedent that I can think of in Australia where an entire region has stood up on an issue like this right across the board – business people, farmers, indigenous people, tree-changers, mayors climbing tripods, Anglican Ministers – all were there.”

Annie Kia sees in the victory an emerging phenomenon of spontaneous democratic energy.

“I think the mainstream press is really starting to show an interest in the diversity of the people involved in this movement. Our opponents have very active PR components that continually characterise us as a small bunch of extremist hippies,” Kia says. “But they are just absolutely incorrect because we really are a collaboration of all different kinds of people. So I think that the media are starting to look at it in a new way and the country people that are stepping up to defend our common heritage are becoming more confident and becoming wonderful advocates.”

Above all though, she attributes this astonishing victory to the thousands who turned up. “I believe we would have had 10,000 people there, ready to face a thousand police. We were growing exponentially and there were mass movement dynamics at play there.”

Aidan Ricketts sees an opportunity from the result to rigorously examine our democratic institutions. “The Bentley victory is worth celebrating and spreading to other communities, but it’s worth continuing to assert that Australia is in a democracy crisis. This corruption being revealed at ICAC is really the tip of the iceberg. It can reveal illegal corruption, what it can’t reveal is the business-as-usual conflation of political and mining interests in Australia,” he says.

“When the tiny town of Bulga won its court case against Rio Tinto on socio economic and environment grounds, the response of the NSW government was two things. One to join as a party in the appeal against the town and secondly in any case to change the legislation, so social and environmental grounds were no longer significant compared to economic grounds. So even when they went on to lose in the Court of Appeal in the second round, it didn’t matter because they could put a new DA in and go through the process of getting the NSW government approval under the new legislation written in their favour.”

Ricketts does see existing solutions to this problem, but believes they’re just a starting point for a comprehensive overhaul of a system that’s broken. “I’m reasonably satisfied that with the Greens we’ve got one significant effective political party that is not captured by the mining and fossil fuel industry or the global media corporations,” he says. “But I think what we need to invest our energy not so much in focussing on parliaments, politicians and political parties and elections, but focussing on building empowered and effective community networks and social movements, because you get maximum bang for your buck from social movements. Lock the Gate is rapidly transforming from a coal and gas focussed campaign to be the battering ram of the pro-democracy movement in Australia.”

Annie Kia is in no doubt as to the direction the pro-democracy movement should move in. “I think our future is in reaching out to people in cities to invite or help them touch base with what our common heritage is – our common farm lands that feed us all, our water supplies that are at risk, our catchments and our common heritage in terms of cultural and wild places,” she says. “The assault on these life support systems is so extreme at the moment that we need to reach into the cities and find a way to work with people there, to defend these things together.”

Learning to live simply

When local Newrybar resident Jess Gilmore first found out about the possibility of unconventional gas-mining coming to the Northern Rivers, she was so distressed she couldn’t sleep for three days – so she decided to take action, spending some weeks out at the protest site either by herself, with her children and with her husband. It was, she writes, a journey of discovery.

“The alarm wakes me at 4.30am, and already I’m feeling excited. I sneak out of the tent and boil the kettle. Around me, I can hear the sounds of tent zippers and car doors opening. We wake our children and with breakfast and supplies in the backpack we are joining the procession of torchbearers on our walk to Gate A to greet the dawn.

Some days there would seem to be just a few of us, sitting around the fire, in the dark, in the cold, in the wet… and as the night lifted and dawn began to break we would see past the circle of firelight and see so many more…a neighbour, a local shop owner, someone I went to school with, a colleague, and many more. The community that formed around Bentley was amazing, inspiring, beautiful.

When I first found out about the possibility of unconventional gas-mining coming to the Northern Rivers, I was so distressed I didn’t sleep for three days. Everything about it felt so wrong. I was heartbroken at the prospect of what kind of legacy we were leaving for our children, and their children’s children. I was busy – two small kids, working, and living on the land with acreage to maintain – but I could not sit by and do nothing. I couldn’t bear the thought of my children asking me in the future why I hadn’t been able to stop it, and having to look in their eyes and say, “I was too busy.” For our family, there was no option. We had to support the Bentley blockade.

It was a juggling act – my sister and I set up camp in March, with one tent for us to share. We would tag team – she would spend a couple of days there, then come home and I would head out. My husband was wonderful, taking on more and more of my responsibilities at home, and caring for the kids when I was at camp. It was heartbreaking when my children didn’t want me to leave home, or wanted to come with me but couldn’t…I was doing it for their long-term future, but they were too young to understand that.

During the school holidays we took our camper out to site and camped as a family. It was a huge experience for us. We had many serious conversations about our children not being there if the rig came or the police arrived, and about one or both of us potentially being in an arrestable situation.

It’s four months since we packed up camp and came home, and life returned to ‘normal’. I say ‘normal’ because things have changed. Our time at Bentley changed us. We want to live…differently. More closely attuned to the land, to nature. We want our kids to grow up feeling connected to place. We want a better way, and we are actively out to make it happen. We want to live simply and contribute meaningfully.

Just yesterday I sat with my boys on the verandah to listen to the birds and watch the mist rising through the valley at dawn. My three-year-old remarked out of the blue, “Mumma, it’s just like Bentley.” I don’t know how much of the experience they understood, but they certainly tuned in. They have witnessed our joy at joining with community to save something precious. They have listened patiently while we explained our responsibility to protect the Earth, and I believe they intrinsically ‘get it’: they have the wisdom of children. They cannot understand why we would plunder the planet we need to sustain us; as our older boy said: “If trees make the air we need to breathe, why would people chop them down?” They have made friends, and had some fantastic fun. They have been part of something amazing.

Our time at Bentley has enriched our family, and made us wiser. It has given us a greater appreciation for the environment and the community that we live in, and that sustains us. And beyond that, it has given us hope.”

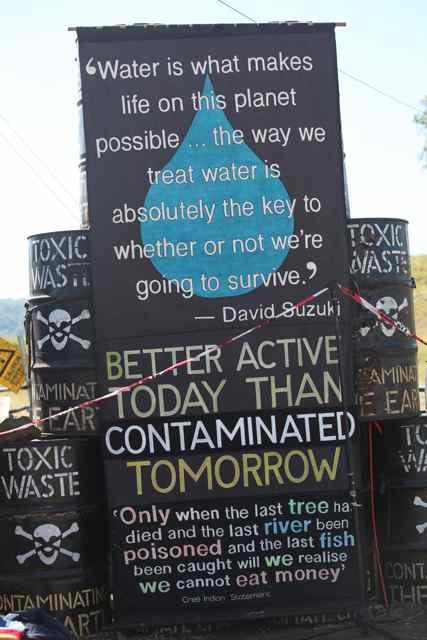

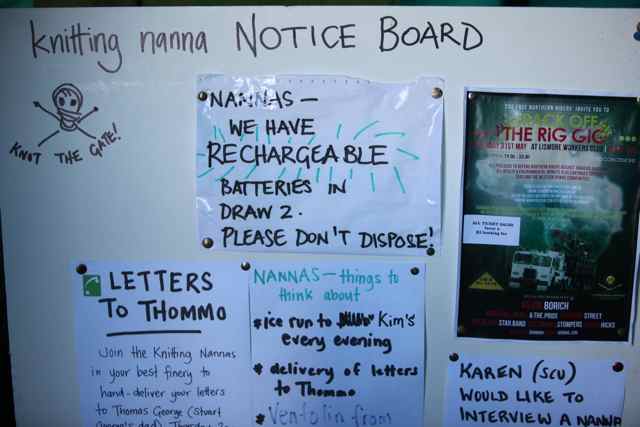

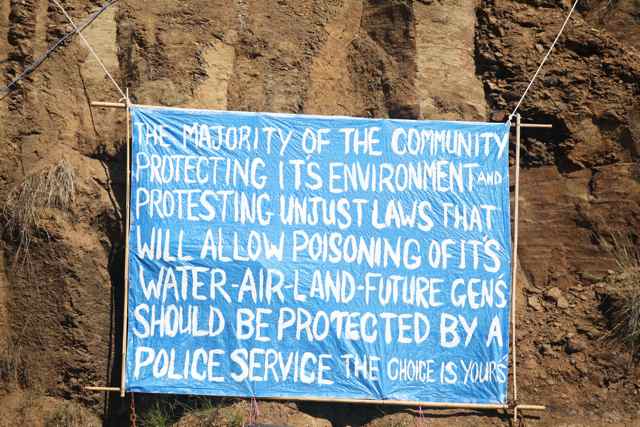

Images of Bentley