Paris, France: People congregate around pens and candles during a vigil at the Place de la Republique(Dan Kitwood/Getty Images)

There is a terrible, truth-is-stranger-than-fiction story involved in the Charlie Hebdo massacre in which 10 employees of the magazine and two French police officers died this week, one of whom was Muslim. Those dead included co-founder and cartoonist Jean Cabut, editor-in-chief Stéphane Charb Charbonnier, deputy chief editor and economist Bernard Maris and cartoonists Georges Wolinski and Bernard ‘Tignous’ Verlhac, writes Candida Baker.

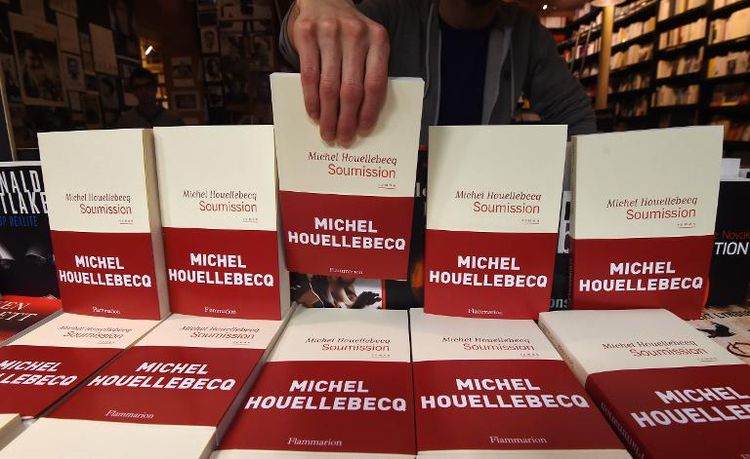

The latest issue of the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo to hit the stands in the week of the massacre featured Michel Houellebecq on its cover. The controversial author, film-maker and poet’s latest novel, Soumission, (submission) portrays a future in which Islamists win the French presidency and set about dismantling the democratic freedoms of the country. Not unnaturally it has shot up to the top of the French best-seller lists (it is due to be published in English in September this year).

Some commentators have complained that the novel simply fans right-wing fears, but in fact Houellebecq’s satire is more about the venality of modern man. His main character, Francois, happily adapts to the new regime – partly because he can be polygamous, and partly because the new Saudi owners of the Sorbonne, where he is employed, pay better. No matter that the novel is about adaptation as much as it as about appropriation, Houllebecq, a friend of the economist Bernard Maris who was one of those killed, is now under police protection, as is his publisher. No doubt Houllebecq’s book and its subject matter, and Houllebecq himself who moved to Ireland for several years after he was accused – and acquitted of racial hatred – will incite fierce opinion on both sides of the provocation anti-provocation fence.

But whatever we think of Houllebecq and his work, and his uncanny literary prescience, the same tenet applies to him as an individual as it does to Charlie Hebdo as a magazine – and it is a simple tenet – they are allowed to publish such material in the country in which they live.

I have been a journalist for over thirty years. I’ve never been, I’d be the first to admit, a ‘front-line’ journalist. My areas of interest have always been the soft, rather than pointy, ends of journalism, and the arts is my most natural home. However, I cut my eye-teeth typing transcripts on an English weekly current affair program, Weekend World, which employed a stellar group of journalists including Peter Jay, (who later become the UK ambassador to Washington), a young Christopher Hitchens, and the journalist and broadcaster Mary Holland who covered the political violence in Ireland for many years. Holland, whom I admired from afar, wrote of the IRA bombing of London’s Canary Wharf in 1994: “There are many forms of censorship and, from personal experience, I know that self-censorship by journalists of what they write and report is the most corrosive, at least in a democracy, where theoretically there are few restrictions on the freedom of the press.”

Over the years I have watched fearless journalists with awe. Journalism is an odd multi-layered profession – it can involve anything from bringing down corrupt governments to covering Hollywood celebrities and their seemingly never-ending trail of marriages. Between the war zone and botox coverage is a medium most journalists inhabit – the place where we practice our need to communicate that which interests us to a wider world. Personally, despite a brief flirtation with the idea of becoming a war correspondent after I watched Nick Nolte in Under Fire, I’ve only been in danger a few times, once when I was covering the first (and only) Himalayan car rally, and somehow we were suddenly in the middle of a crazed mob hell-bent on throwing stones, and worse, at us. I can’t say I enjoyed it much. Arts journalism doesn’t come in for much attack generally, although Jack Hibberd once took offence at an article I wrote for The Age saying he was wearing a ‘sartorially’ elegant suit, because, he said, it suggested he had money. He never spoke to me again. It was hurtful, but hardly life-threatening. From time to time as a writer or editor I’ve had to fight for a story, but I have been fortunate to work and live in what has generally been a comfortable world.

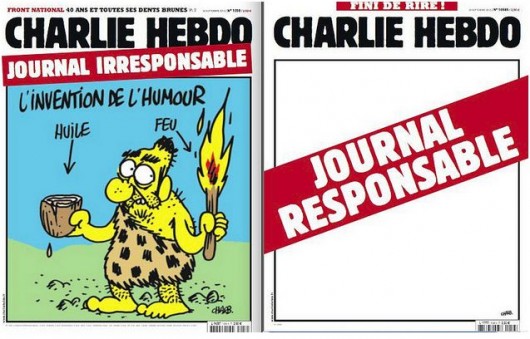

The staff at Charlie Hebdo practiced absolute freedom. Their habit of satirizing religious leaders and their particular glee in lampooning the Prophet was always going to ensure they were under scrutiny from Islamic extremists. In 2006 it reprinted cartoons of Mohammed from a Danish newspaper that had caused ripples of fury across Europe. In 2011 its offices were fire-bombed when it published a cartoon of Mohammed under the title Charia Hebdo. You could say it was asking for trouble. In another earlier age it might well have been censored, or shut down, or banned. But in France, since it began in 1970, it has been a beacon for the phrase, ‘Freedom of the Press’.

But let me state up front, I’m not a Charlie Hebdo reader – I don’t live in France, my French is good but not fluent, and I’m not an avid devourer of hard news, politics or satire, although I appreciate all those as part of a balanced journalistic diet. However as Evelyne Beatrice Hall once wrote, under her pseudonym of S. G. Tallentyre in her biography of Voltaire: “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” (A quote, coincidentally, which is often misattributed to Voltaire himself, but which Hall used to illustrate Voltaire’s beliefs.)

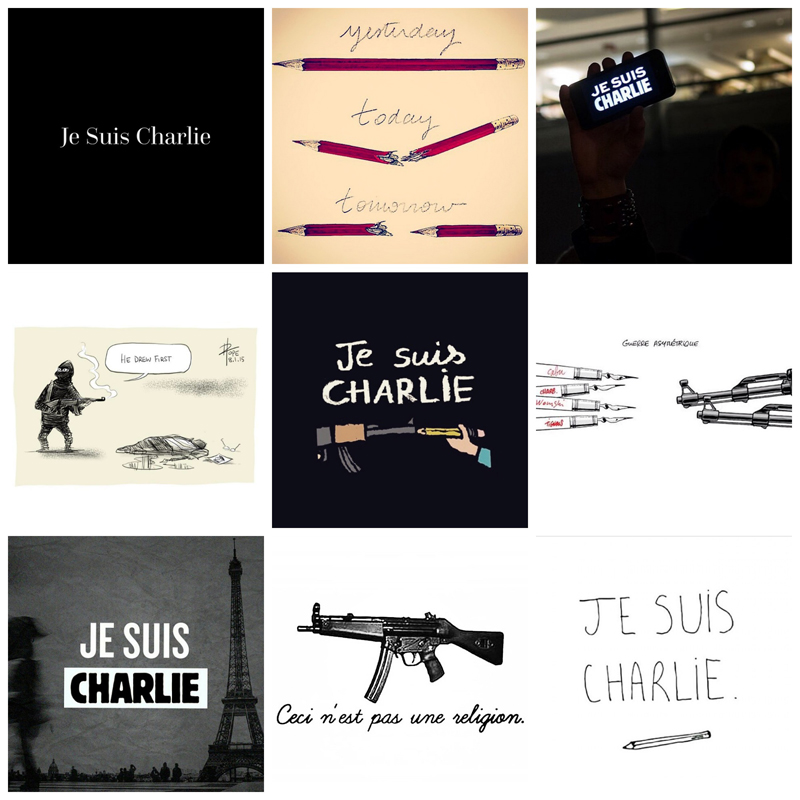

It’s this idea of defending the right of people to write and publish what they want – within the laws of their country – which is in part, I think, responsible for the extraordinary outpouring of solidarity around the world and the adoption of ‘Je suis Charlie’ – ‘I am Charlie’.

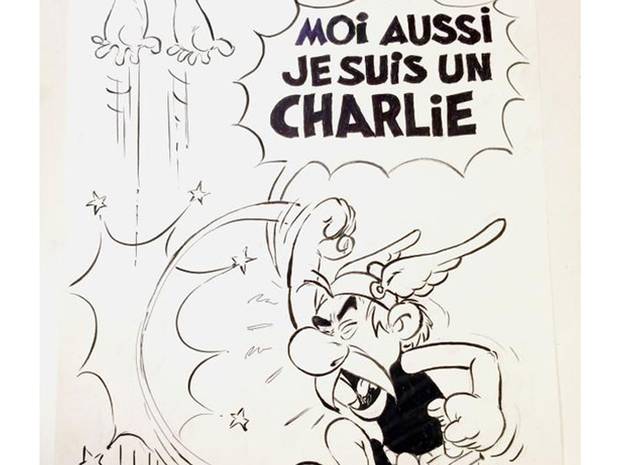

Why ‘Je suis Charlie’? It seems to me that beyond the obvious meaning – there is a plurality of meaning which speaks to us. The French verb suivre – to follow – also fits the meaning. ‘I follow Charlie’. So ‘Je suis Charlie’ can be read either as the moi aussi intention – ‘I am Charlie and if you attack the magazine Charlie Hebdo you attack me’ – or more simply as ‘I follow Charlie’. Two days after the September 11 attack in New York the French newspaper Le Monde published an editorial ‘Nous Somme tous Américains’ (‘We are all Americans’), and it’s that notion of connection (we are all the same) that has resonated so strongly with millions of people around the world. One of the thousands of cartoonists to offer support is the 87-year-old Albert Uderzo, the creator of Asterix who has come out of retirement to create a ‘Je suis Charlie’ cartoon.

In the continuing dreadful aftermath of the massacre – the shooting of the two Kouachi brothers, Said and Cherif, and of the IS member Amedy Coulibaly who took hostages at a kosher supermarket the next day, and the death of four hostages, France is standing by Charlie Hebdo en masse. (So far the world too is standing by moderate Muslims, and long may that continue.)

The magazine plans to raise its print run from 60,000 last week to a million next week, and although the magazine was offered work by cartoonists all over the world, the decision has been made to run an eight-page edition using only the remaining staff. The newspaper Le Monde has promised cash to help them meet the half-million-euro production cost; Liberation Magazine, which helped them after the 2011 firebombing is giving them office space.

The French President, Francois Hollande, said that there was no question that Charlie Hebdo should be given all the help it needed to continue publication. If there was an aim by the killers, beyond the murderous act itself I imagine it must be to attempt to silence, or soften, the Western media’s coverage of Islam. But as the Economist so rightly put it: “Nothing can be done with a pencil or pen that warrants a reprisal with a Kalashnikov.”

It was after 2011 firebomb attack that editor and cartoonist Stéphane Charbonnier (Charb) said: “I’d rather die standing than live on my knees.” His partner, Jeanette Bougrab, a member of the French National Council of State who served under Nicholas Sarkozy’s regime, said Charbonnier knew he would be assassinated. “He never had children,” she told media, “because he knew he was going to die. He lived without fear, but he knew he would die.”

In the end, even though in the Byron Bay hinterland where I live, there is more likelihood that I will die from a car accident, a bee sting, or even a shark attack than a terrorist attack, in solidarity, in connection, and in remembrance – ‘Je suis Charlie, aussi’.