Robert Drewe discovers that his father’s favourite expression doesn’t really suit, or belong, to its hapless bird namesake at all.

Some drongo almost smashed my study window the other morning. I was writing away when there was an explosive thump a couple of metres from my head and the glass nearly burst from the window frame. Outside, lying on its back, was a big bird with glossy black feathers and iridescent purple and blue highlights. One blood-red eye was open and staring sightlessly up at me.

It was the first actual drongo to impinge on my consciousness: a spangled drongo, according to the Field Guide to the Birds of Australia, and immediately I thought of my father, for whom a holiday car journey never passed, nor an assisted session of maths homework, that didn’t contain many vehemently-expressed variations of “Drongo!”

We grew up knowing its meaning: idiot, simpleton, harmless fool. But if a drongo were to have physical form, it sounded more like a creature out of Lewis Carroll, lumpish, slow and turtle-shaped, than the black and purple bird lying prone before me. We didn’t have them in Western Australia, not bird drongos anyway. But now I know what they look like, I see that I’m surrounded by drongos here in the Northern Rivers. Indeed, at this moment, two more drongos are dashing about in the shrubbery after bugs, soaring aerobatically up into the palms and sucking nectar from the grevillea bushes.

While boisterous, noisy and occasionally mystified by window glass, the behaviour of Dicrurus bracteatus is not really foolish enough to merit its name becoming a national byword for stupidity. Actually they look quite adroit and clever. So how did this happen? Field Guide gives no explanation, and Wikipedia, while repeating that drongo is Australian slang for idiot, lamely suggests as a reason “the bird’s uninhibited and sometimes comical behaviour as it swoops in search of insects.”

I turned to the Australian National Dictionary Centre of the Australian National University, which shot down that theory. “The origin of this term has been wrongly traced to the bird called the drongo…Some of the drongos of Queensland are migratory, and in winter travel north to New Guinea or south to Victoria. One ingenious theory has it any bird which travels to Victoria in winter must perforce be stupid, but there is no convincing evidence that the drongo acquired the reputation of the galah.” (A bit rich, that, coming from Canberra, national centre of icy winters.)

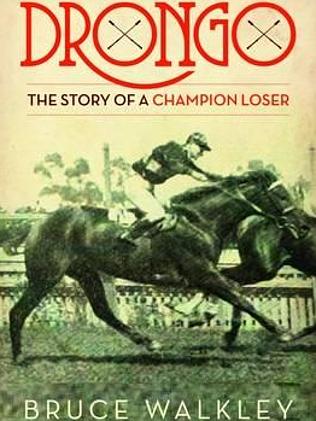

The ANU goes on to assert that the origin of drongo as no-hoper belongs with a famously unsuccessful race horse, Drongo, in the 1920s. He often came very close to winning major races, coming second in a VRC Derby and St Leger, third in the AJC St Leger, and fifth in the Sydney Cup, but in 37 starts never won a race. Tradition had it that soon after Drongo’s retirement, racegoers began applying his name to other unlucky horses, and then by extension to humans who were slow, clumsy or hopeless cases.

This explanation only partly convinces. The horse wasn’t unusually hopeless; many horses never win a race. And there was a 15-year gap between the end of Drongo’s racing career and the first proven use of drongo in the transferred pejorative sense. This was in the early 1940s when RAAF personnel began applying the term to slow-learning World War II recruits. But the air-force connection at least cleared up for me my ex-pilot father’s daily use of the term.

I reckon the slur caught on because to the Anglo-Saxon ear “drongo” sounds amusingly stupid. And so to the drongo lying belly-up outside my study window. In the way of hurt birds it looked strangely vulnerable. Dead or alive? What to do? I was considering my mother’s successful remedy for window-concussed birds: a droplet of Johnnie Walker administered to the beak with an eye-dropper, when the drongo opened its other ruby eye, shook its head to clear it, glared at me for a moment, smoothed its forked tail feathers, and strolled nonchalantly away.

Then it took to the air. It didn’t look silly or stupid or worth the nation’s insults; it looked pretty much in control of events. More than, say, a galah in a similar situation. Of course galahs have it even worse.

Robert Drewe’s latest book, The Beach, an Australian Passion, is published by the National Library of Australia and is available here: the-beach-an-australian-passion

His other recent books The Local Wildlife and Swimming to the Moon are on sale here: penguin.com.au