Verandah Magazine publisher Candida Baker ponders the many meanings of Easter, and tries to unravel a myth that can include the resurrection of Jesus, chocolate eggs and an Easter Bunny.

A few years ago, around this time of year, one of my friends, who’s from a good Catholic family, decided it was time she and her non-Catholic husband took their children to Italy to see Rome in all its pomp and circumstance. She knew, she said, that she’d rather let the religious educational side of things down when her eight-year-old son said to her, “Mum, who’s this bearded dude, and why’s he hanging up on a cross?”

She was so shocked she sat him down then and there and gave him a potted history of Christianity, the crucifixion and the resurrection. He thought about it for a minute. “It’s quite a good story,” he said, “but I think I prefer the Easter Bunny.”

Of all the festive occasions we celebrate in a year it would have to be said that Easter is perhaps the most confusing. I mean, when you think about it, how on earth do you actually put rabbits, chocolate, eggs, the crucifixion and the resurrection into three short days?

To put on a feminist hat for a moment, Easter is one more example of a pagan celebration that was originally connected to women, but was hijacked over the centuries by the patriarchy to the point where I think you would have a hard time finding even one child who would know that in fact Easter was originally a celebration of spring and fertility. Its name comes from the Saxon goddess of the dawn and spring – Oestre or Eastre, who was known also in Germany as Ostara, Easter connecting to the word ‘estrogen’, or oestrogen, to give it its older spelling – a word given to the group of hormones that regulate women’s menstrual cycle. In Saxon times April was called ‘Ostermonud’ the month in which the cold winds of winter stopped, and the spring began.

Ostara, also known elsewhere as Ishtar, had a passion for new life, and her symbol was the rabbit, with its propensity for rapid reproduction. As for eggs – well, once you begin to see the Easter we celebrate as two separate events, (albeit curiously connected) the death and resurrection of Christ, and a celebration of spring and fertility – then eggs are an obvious symbol of fertility, and baby chicks a cheerful symbol of that new life. Always celebrated on the first full moon after March 21st to mark the arrival of spring, brightly coloured carved eggs, chicks and bunnies all made an appearance, as well as dyed or decorated eggs. Chocolate eggs arrived on the Easter scene in the early 19th century in Europe, and it was John Cadbury who hit on the jackpot – producing Cadbury’s first chocolate Easter eggs in 1875.

As for the Easter egg hunt, it may well have originated in Europe as the Christians began to persecute the followers of the ‘old ways’. Instead of giving the eggs as gifts to the children, the adults hid them, as they had to hide their religion, and the children had to find them.

Another forgotten Easter practice is eating ham, which we normally associate with Christmas, of course, and even then it is a strictly ‘Christian’ meat, forbidden under the religious laws of Judaism and Islam. Having butchered their meat during the previous autumn so they would have food throughout the winter months, pagans and Christians both used the Easter period as a time to eat the last of the salted, cured meats, and to celebrate the fact that hunting season had arrived. Even the Christian practice of Lent can be traced back to the pagan practice of fasting at the time of the spring equinox, clearing the body of toxins in time for spring.

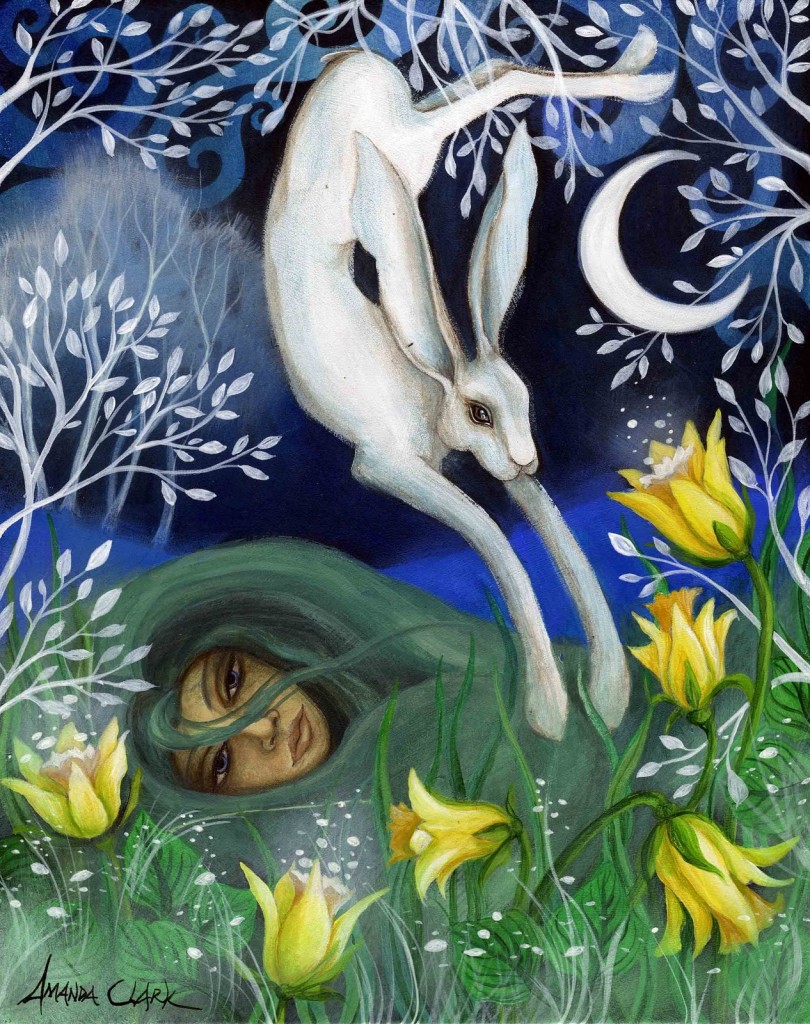

Personally, I think it’s a loss to the collective imagination of the world that the wonderful myth associated with the Easter Bunny is not taught to children. According to legend, feeling guilty about the late arrival of spring, the Goddess Ostara saved the life of a bird whose wings had been frozen, and kept him as her pet, (and in some versions, her lover) and because he could no longer fly she turned him into a snow hare so he would be able to run from hunters. But in remembrance of his earlier life, she also gave him the ability to lay eggs, in all the colours of the rainbow, one day a year. When the hare angered her (and rumour has it she was quick-tempered) she cast him into the sky as the constellation Lepus (The Hare), where he remains forever at the feet of the Orion. The hare was allowed to come back to earth once a year, but only to give away his eggs to the children at the Ostara festivals. And all of that linked into how important the hare was to many ancient traditions – associated with various moon goddesses and deities of the hunt.

Somehow the innocent hare and rabbit, honoured for their fertility, came to grief under Medieval Christians who determined that witches changed into rabbits in order to suck the cows dry, and that witches could be killed by a silver crucifix, or later a bullet, when they appeared as a hare. Given hares ‘mad as a March hare’ behaviour and their ability to produce up to 42 offspring each spring, it’s understandable that they came to represent excess in general. (You could call that a bit of an ah-hare moment.) Later though, Christianity reclaimed the hare as a symbol of purity, with a white hare at the Virgin Mary’s feet, representing the triumph of virtue over lust.

The connection between Jesus and rabbits comes through the delightful Christian legend about a young rabbit, waiting for his friend Jesus to return to the Garden of Gethsemane, unaware of what has happened to him. Early on Easter morning, Jesus came back to his favourite garden and was greeted to an ecstatic welcome by his little friend. When the disciples came into the garden to pray, unaware of the resurrection, they found a clump of larkspurs, with each blossom bearing the image of a rabbit in its center as a remembrance of its hope and faith.

There’s also, of course, Eastern versions of all these stories – some of them contained in the one of the oldest stories ever discovered, the Babylonian story of Gilgamesh. Ishtar, the goddess of romance, procreation and war in ancient Babylon, was also worshipped as the Sumerian goddess Inanna, known as a ‘mother goddess’, and has the same linguistic derivation as the Northwest Semitic Aramean goddess Astarte. Ishtar’s sister, Eresh-Kigel, was the ruler of the Underworld, and was the goddess of the opposite forces – death and infertility. Eresh-Kigel kidnapped her sister’s lover, Tammuz and forced him to live half the year in the underworld (similar, of course, to the Greek myth of Demeter and Persephone). Ishtar went in search of Tammuz and had to make some pretty heavy threats to Eresh-Kigel before she was allowed into the Underworld to plead for her lover’s return. While she was away from earth, everything shriveled and died, and in various forms of the legend, either Ishtar herself died and was resurrected, or was kept captive in the Underworld for – yes, you guessed it – three days and three nights, her return marking her resurrection, and the arrival of spring.

So there we have it – Easter eggs, the Easter Bunny, the dawn that arrives with resurrection of life, and the celebration of spring all serve to remind us of the cycle of rebirth and the need for renewal in our lives. In the history of Easter Christian and pagan traditions have become so interwoven that it is hard to tell where one story starts and another story ends. Finally, of course there’s the ‘bearded dude’ – who calls us, whatever our faith, to think about what God means to us, and the promise of eternal life.

Easter[nb 1] (Old English usually Ēastrun, -on, or -an; also Ēastru, -o; and Ēostre),[1] also called Pasch (derived, through Latin: Pascha and Greek Πάσχα Paskha, from Aramaic: פסחא, cognate to Hebrew: פֶּסַח Pesaḥ),[n (source Wikipedia)